From the 14th to the 17th century, Europe had an era known as the Renaissance, which was marked by significant artistic advancement. During this historical period, a significant number of paintings of women were produced.

These paintings depicted a wide variety of topics, including biblical and mythological figures, as well as portraits of noblewomen.

These paintings are distinguished by the meticulous attention to detail, vivid color use, and deft manipulation of light and shadow that they feature.

They reflect a significant growth in the world of art, with artists experimenting with new techniques and styles to create works that are still recognized and studied today.

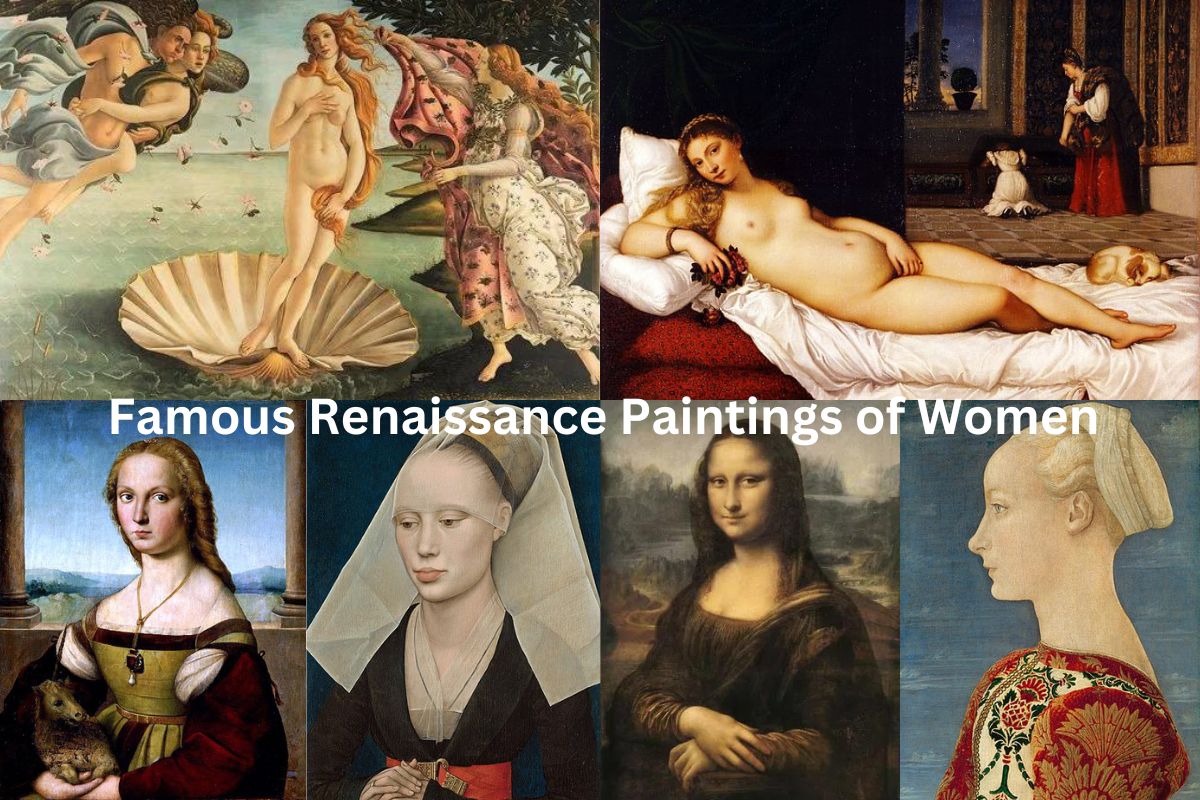

In this light, the paintings “Mona Lisa” by Leonardo da Vinci, “The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli, and “Venus of Urbino” by Titian are among the most well-known examples of female subjects in Renaissance art.

Famous Renaissance Paintings of Women

1. Mona Lisa – Leonardo da Vinci

This painting by Leonardo da Vinci has always been regarded as one of the most fascinating works of art in the world. It is also one of the most widely copied works of art, with innumerable copies existing in a wide range of sizes and mediums.

Lisa del Giocondo, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo and the mother of his two children, is the subject of the famous Mona Lisa painting. Between 1503 and 1505, Leonardo da Vinci began working on it, and he completed it in 1519.

Louis XIV, King of France, had the Louvre Museum established in 1637, and this is where the picture is now housed.

Also Read: Mona Lisa Facts

Though widely known among art experts, the public didn’t become familiar with it until 1911, when an Italian employee named Peruggia stole it from the Louvre.

Peruggia, a staunch Italian nationalist, believed the masterpiece belonged in an Italian museum rather than a French one and should be sent there.

It was returned to the Louvre after being Peruggia’s arrest and the paintings recovery, and now it draws thousands of visitors every day.

It’s hard to imagine that this painting is 400 years old because it’s so flawless.

2. The Birth of Venus – Sandro Botticelli

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus is often regarded as one of the best pieces of art to emerge from the Renaissance period. It shows the Roman goddess Venus being borne ashore on a massive shell.

The Primavera, which was created by Sandro Botticelli and is another well-known piece of art from the Renaissance, also has an iconic and mythological connotation.

The Medici were a powerful financial dynasty in Renaissance Florence, and they were responsible for commissioning these two masterpieces.

In contrast to the bulk of paintings that were created during that time period, “The Birth of Venus” was painted on canvas using tempura.

Canvas is a great material because, unlike wood, it does not warp when exposed to moisture and hence retains its shape.

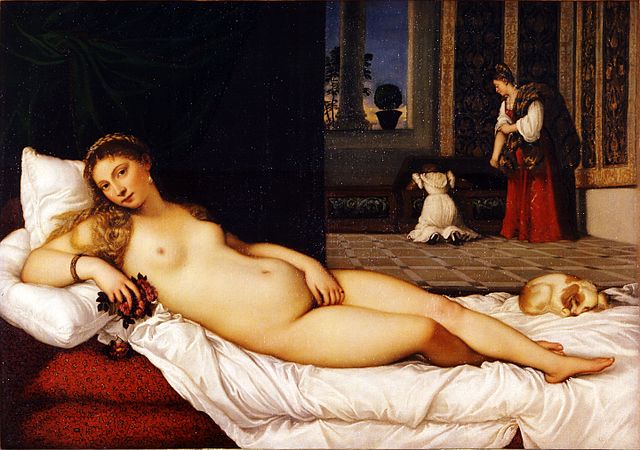

3. Venus of Urbino – Titian

An oil painting that is often referred to as Reclining Venus or Venus of Urbino and was completed by the artist. It’s thought that work on the Venus of Urbino began in 1532 or 1534, that it was finished in 1534, and that it was sold in 1538.

It depicts a young woman, who is widely identified as Venus, lying naked on a plush sofa or bed that dates back to the Renaissance era. The time period shown in this piece is the 15th century.

It can be seen right now in the Gallery of the Uffizi, which is located in the city of Florence.

When Titian completed the background for the painting, Giorgione’s Venus of Dresden served as the source of inspiration for the position of the subject in the picture.

Titian has tamed Venus in this painting by depicting her in a setting that is more intimate, by having her engage in conversation with the viewer, and by putting the emphasis on the allure that can be gained from her feminine beauty.

4. Sacred and Profane Love – Titian

Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love is an oil painting that was probably finished around the year 1514, when he was still in the early stages of his career.

It is reported that Niccol Aurelio, a secretary to the Venetian Council of Ten, whose coat of arms appears on the tomb or fountain, commissioned the painting to honor his marriage to a young widow named Laura Bagarotto.

It could be a representation of the bride dressed in white and sat next to Cupid while being led by Venus, the goddess of love.

The picture has been interpreted in a number of different ways by a number of different people. Their first task is to discern the purpose of the artwork, which the vast majority of contemporary views understand to be paying tribute to a marriage.

The next step is to assign identities to the figures that are the same in every other way but for their clothing; once this is done, the parties can no longer reach a consensus on anything further.

In recent years, there has been a trend to disregard elaborate and cryptic interpretations of Titian’s (and other Venetian artists‘) iconography.

However, in this particular instance, a straightforward interpretation has not been established, and historians are more willing to accept allegorical alternatives that involve a significant amount of complexity.

5. Portrait of a Lady – Rogier van der Weyden

Portrait of a Lady is a tiny oil-on-oak panel painting by the Netherlandish painter Rogier van der Weyden, completed around 1460.

The geometric shapes that define the lines of the woman’s veil, neckline, face, and arms, as well as the fall of light that illuminates her face and headdress, constitute the foundation of the composition.

The model’s almost unnatural beauty and Gothic grace are enhanced by the striking contrasts of darkness and light.

Van der Weyden was focused with commissioned portraits towards the end of his life, and his incisive evocations of character were highly acclaimed by subsequent generations of painters.

The woman’s humility and guarded temperament are represented in this piece by her frail stature, lowered gaze, and tightly clenched fingers.

She is slim and shown with elongated features, as seen by her narrow shoulders, carefully pinned hair, high forehead, and the intricate frame established by the headgear.

It is the only known portrait of a lady regarded as an autograph work by van der Weyden, although the sitter’s name is unknown and the painting is untitled.

6. Portrait of a Young Woman – Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Piero del Pollaiuolo

Portrait of a Young Lady is a 1470-1472 mixed-media work on panel ascribed to Piero del Pollaiuolo or his brother Antonio. It is now on display in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan, which utilizes the painting as its logo.

The painting is one of the most iconic and well-preserved Renaissance portraits of a woman in profile by one of the two Pollaiuolo brothers.

It is frequently likened to the Uffizi’s Portrait of a Woman, as well as similar pictures in the Staatliche Museen, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Portrait of a Girl by Andrea della Robbia has similar facial features.

Traditionally, these works have been credited to Piero del Pollaiuolo, although modern critics, such as Aldo Galli, have offered attributions to Antonio.

The woman is presented against a blue sky furrowed by clouds. In the usual genre of Italian court portraits, she stands in profile, combining humanistic aspirations with the form of Imperial Roman medals.

Following the classical principles of the Renaissance, the airy atmosphere represents a harmony between nature and feminine beauty. The image terminates at the woman’s shoulders, with a slight twist of the torso revealing her neckline.

The face is strongly separated from the background by a distinct, expressive line, which is typical of Florentine art from the second half of the 15th century, particularly the Pollaiuolo brothers. Overall, the portrait is an emblem of 15th-century Florentine beauty.

7. Young Woman with Unicorn – Raphael

Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Lady with a Unicorn was completed between 1505 and 1506. It is located in Rome’s Galleria Borghese. The painting was initially painted on panel before being transferred to canvas in 1934 during conservation work.

Over-painting was removed during this repair, revealing the unicorn and removing the wheel, cloak, and palm frond that had been applied by an unknown painter in the mid-17th century.

Before the first twentieth-century restoration, the picture depicted Saint. Catherine of Alexandria with a wheel and a palm frond.

The picture’s composition—the figure in a loggia opening out onto a landscape, the three-quarter length format—was apparently influenced by Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, which he painted between 1503 and 1506.

Until recently, the work’s authorship was unknown. The subject of the picture was recognized as Saint Catherine of Alexandria and attributed to Perugino in the Gallery’s inventory in 1760.

The picture was restored in 1934-36, and the removal of excessive repainting revealed the unicorn, generally a sign of purity in medieval romance, in place of a Saint Catherine wheel.

In 1959, radiography discovered the image of a little dog, a symbol of conjugal loyalty, beneath the unicorn during restoration work on the painting. It served as a rough sketch for the unicorn’s final look.

8. Portrait of Ginevra de’Benci – Leonardo da Vinci

Ginevra de’ Benci is a portrait of the 15th-century Florentine noblewoman Ginevra de’ Benci by Leonardo da Vinci.

It is Leonardo’s sole painting on show in the Americas, and it is housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The sitter in the portrait is commonly thought to be Ginevra de’ Benci, a well-known young Florence lady. Leonardo completed the painting between 1474 and 1478 in Florence, likely to commemorate Ginevra’s 16th year of marriage to Luigi di Bernardo Niccolini.

Lady portraits in the modern era were frequently commissioned for one of two reasons: betrothal or marriage. Wedding paintings were usually taken in pairs, with the lady on the right facing left and the man on the left facing right; because this image faces right, it is more likely to imply betrothal.

The juniper shrub that surrounds Ginevra’s head and takes up the majority of the background has a purpose other than decoration. In Renaissance Italy, juniper was considered a sign of feminine virtue, and the Italian phrase for juniper, ginepro, is also a play on Ginevra’s name.

The painting is one of the National Gallery of Art’s centerpieces, and many people enjoy it because it depicts Ginevra’s demeanor. Ginevra is attractive, but her demeanor is solemn; she doesn’t smile, and her gaze, while forward, appears uninterested in the audience.

Ginevra’s arms and hands are assumed to have been lost since the bottom of the painting was removed at some point, maybe owing to deterioration.

9. Lady with an Ermine – Leonardo da Vinci

Cecilia Gallerani, who was Ludovico Sforza’s mistress, commissioned the painting known as “The Woman with an Ermine” for her own personal collection. She is said to have posed for Leonardo da Vinci as he was creating this piece of art, as the tale has it.

A woman is shown in the picture sitting in a relaxed position, with one hand resting across her lap and the other cradling an ermine.

Because of its stunning appearance and the intrigue that surrounds it, “Woman with an Ermine” is considered to be one of the most famous portraits ever created by Leonardo da Vinci.

The composition is a pyramidal spiral, just like in many of Leonardo’s works, and the sitter is captured in the process of migrating to the left. This reflects Leonardo’s lifelong interest in the movement dynamics of various subjects throughout his work.

10. Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting – Artemisia Gentileschi

The Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi painted Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting, also known as Autoritratto in Veste di Pittura or simply La Pittura.

The oil-on-canvas work measures 38.8 in 29.6 in and was most likely created during Gentileschi’s visit to England in 1638 and 1639.

It was in Charles I’s collection before being returned to the Royal Collection during the Restoration (1660). It was displayed in Hampton Court Palace’s “Cumberland Gallery” in 2015.

The scene features Gentileschi painting herself, who is portrayed as the “Allegory of Painting” drawn by Cesare Ripa. It is now part of the Royal Collection of the United Kingdom.

The picture depicts unusual feminist ideas from a time when women were rarely employed, let alone well-known for them.

Gentileschi’s portrayal of herself as the pinnacle of the arts was a daring statement for the time, albeit the picture is now eclipsed by many of Gentileschi’s other, more dramatic and raw themes portraying the artist’s troubled youth.

Michael Levey proposed in the twentieth century that it is a self-portrait as well as an allegory, but it is not universally recognized, as some art historians perceive the features of the person here as too distinct from those in previous pictures of the artist.