Prints are a great way to start or supplement your art collection. Many feel like prints are not really worth it. They think that prints are only copies of the real works.

Prints, yes, sometimes are quality copies of original works, but often, prints are original works themselves. These days art prints are an exciting and inspiring art world all their own. Let’s take a look at the print world from artist proof to final edition print.

What is an Artists Proof?

An artists proof is a portion of the print’s edition of an original artwork is left to the artist. This AP or “artist proof” is left unnumbered, and the artist can do as they see fit with the proof.

Artist proof vs Print

- EA (épreuve d’artiste) means “artist proof” in French

- HC (hors commerce) means “not to sell” in French

- Like artist proofs, they were set aside for the artist and usually used for exhibitions and such to keep the works themselves from being overhandled or damaged.

- They differed from the editioned prints in that they were, at times, printed on different paper or inked differently, but most times, they were identical.

- PP means “printer’s proof”

- These were unnumbered proofs, which were given to printers as compensation or in gratitude.

- At times, there were multiple persons responsible for the printing process, meaning multiple PPs.

- Trial proof

- This is an impression printed to test the image’s development.

- After printing a trial proof, the artist may revise the proof.

- Many trial proofs may be revised before the final proof is made.

- BAT (bon à tirer) means “ready to pull” in French

- This is the proof that has been approved for the final edition.

- There exists only one for each edition.

Are artist proofs more valuable than a print?

Artist proofs are usually of a higher value than the edition’s prints. This is because they are rare. Many times, the artist proof varies from the final edition, making it unique, a trait that entices collectors.

Numbered Prints

X Prints

Antique prints, many of them, have a single number on them, and some get confused and think this means they are “numbered” prints. They are not.

This single number on an antique print is simply a catalog or stock number that was assigned to it when the print catalog or stock list was issued by the printmaker.

The same stock number would show on every copy of that print. The number was on the print in case the framers and printsellers wanted to order prints. They would just order a #X from the publisher.

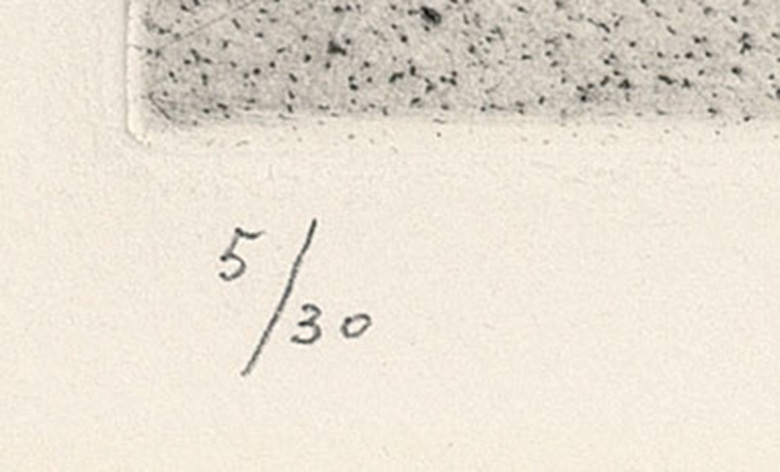

X/Y Prints

A numbered print is indicated by an X/Y in the margin, usually in pencil, meaning a particular print is number X of only Y impressions made.

Say they did only 100 images of a certain work. They would number them 1/100 through 100/100. This practice began as a way to indicate to a buyer that only a limited number of a particular print were available and they were purchasing one of them.

A strategy for marketing prints, the practice does not necessarily speak to the print’s quality or its worth. It simply denotes that it is a limited edition and their print is one of the set number of official prints.

While, again, numbering does not mean a print is fine or valuable, it does give you something to look for. If an artist did number their prints and you get a print that is unnumbered, you know that a couple of things could be happening. One is that it could be a restrike, made later, and it is not from the original series, meaning it has a lesser value. It could also be a reproduction.

The numbering of prints is a relatively new practice only taken up in the late 1800s. There was no need to number prints before this time, due to the fact that all prints were produced in limited editions.

The reason for this is two-fold. First, the way printing worked in the late nineteenth century did not allow a great number of prints to be made at once. Second, the market for prints wasn’t such that anyone would need to run off a huge number of impressions.

In the mid-1800s, too many impressions of a print was just not something artists worried about. Actually, it is something that probably never even dawned on an artist, because of the fact that there was no cause at the time.

However, as time passed and artists realized how having only a limited number of impressions of a print could increase the value of the impressions, numbering became a way of ensuring that a buyer could tell whether they were purchasing an impression from the original run.

Numbering is relegated to fine art prints, which are created to target discerning collectors who would desire that a piece be one of a kind or of very few. Most prints, however, are simply commercial prints that are produced in huge numbers for sale to the public.

Also, note that many artists today do not number their prints, even though they are considered fine prints. Maybe they did not think it would boost their sales or maybe they just wanted to be able to run unlimited impressions. Today, a print can easily be from an official run of a genuine limited edition and not be numbered.

It is simple. The thing you need to know is whether the print in question is from an official run from a limited edition that was numbered or unnumbered. Once you know which it is supposed to be, you will know how to judge the print you are considering purchasing. If the edition was a numbered run of 200 prints, then your print should be (1-200)/200. If the edition was an unnumbered run, then you don’t need to look for a number.