The European art movement known as Mannerism, also known as the Late Renaissance, developed in the years after the peak of the Italian High Renaissance, around 1520.

Its popularity grew rapidly in Italy beginning around 1530 and continued until the close of the 16th century, when it was mostly replaced by the Baroque movement.

There were still several buildings in the early seventeenth century that were decorated in the Northern Mannerism style.

From a purely artistic perspective, Mannerism includes a wide variety of methods that were either directly or indirectly influenced by the harmonious ideals associated with artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Vasari, and early Michelangelo.

In contrast to the proportion, symmetry, and ideal beauty emphasized in High Renaissance art, Mannerism exaggerates these qualities, often resulting in discordant or artificially exquisite compositions.

This school of art, distinguished by its artificial (as opposed to realistic) characteristics, places greater emphasis on compositional tension and instability than earlier Renaissance painting did.

In literature and music, Mannerism is easily recognizable by its overly flowery language and intricate compositions.

Famous Mannerist Paintings

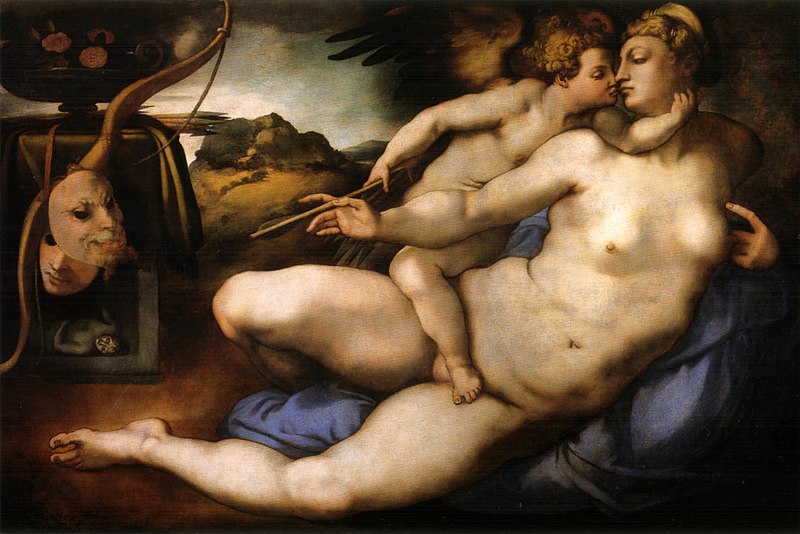

1. Venus and Cupid (Pontormo) – Michelangelo

In Florence’s Galleria dell’Accademia is an oil painting on panel by Pontormo titled “Venus and Cupid” that was likely based on a lost drawing or cartoon by Michelangelo.

Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio also created a copy of this, which may be seen in the Palazzo Colonna in Rome, while the original is on display in the British Museum.

Besides the two at the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples and the two in the Royal Collection at Kensington Palace, there are copies of this painting in Hildesheim, a small version in Geneva attributed to Michele Tosini, and a larger version in Hildesheim, both of which are located in the United Kingdom.

Ottaviano de’ Medici commissioned three reproductions from Giorgio Vasari.

Alessandro de’ Medici bought the painting and had it censored early on to hide Venus’s bareness, as had been done to the Rome copy. Guardaroba medicea inventories in 1553 and 1560 both included it.

It wasn’t until 1850 that the picture was found again, and two years later, restorer Ulisse Forni removed much of the repainting, restoring it mostly to its original appearance (save for the cloth across Venus’s genitalia). In 2002, the cloth was finally erased and the paintings restored to it’s original condition.

2. Madonna with the Long Neck – Parmigianino

Oil on canvas by Parmigianino, dated to between 1535 and 1540, depicting the Madonna and Child with angels; commonly known as The Madonna with the Long Neck.

Painted in 1534 for Francesco Tagliaferri’s burial chapel in Parma, it was unfinished at the time of Parmigianino’s death in 1540.

The Uffizi gallery has owned and displayed it since 1948, after it was purchased by Ferdinando de’ Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany.

Since its recent repair, the unfinished angel’s face near the Madonna’s right elbow has become more distinguishable. The middle angel in the bottom row now examines the vase held by the angel on his right, where a faint image of a cross may be discerned.

This angel viewed the Christ Child from above before the redemption. The alterations performed during the restoration probably accurately match those made to the original artwork, which must have been done at some point in the past.

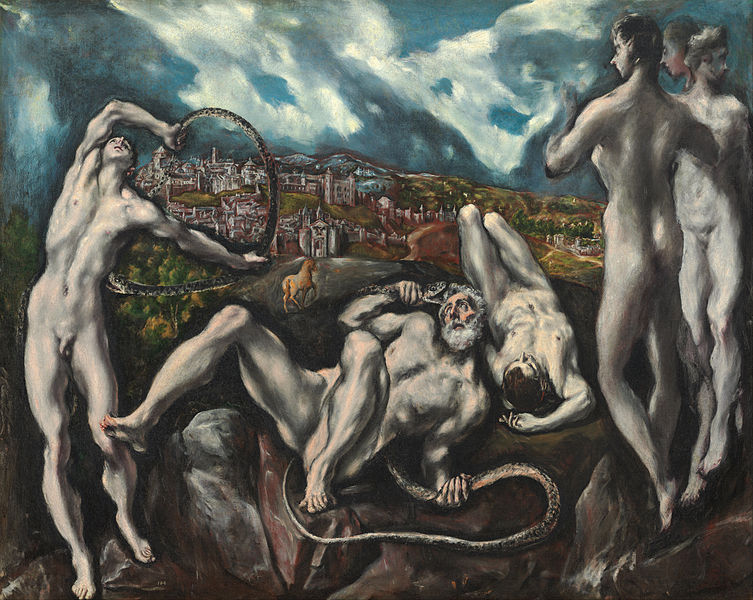

3. Laocoön – El Greco

In 1610, El Greco finished painting The Laocoön. The Washington, DC National Gallery of Art has it as part of it’s permanent collection.

From the perspectives of Greek and Roman mythology, the artwork depicts the mythical deaths of Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus.

Laocoön and his sons were killed by sea serpents as retribution from the gods because he warned his people about the Trojan horse.

As a reaction to the ideals of the Renaissance, the newly discovered Hellenistic sculpture Laocoön and His Sons in Rome inspired the creation of Laocoön in the Mannerism art style of the 16th century in Italy.

Featuring a powerful emotional mood and distorted characters, El Greco’s painting is a deliberate departure from the Renaissance ideal of balance and harmony.

4. The Burial of the Count of Orgaz – El Greco

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, completed by El Greco in 1586, is one of the artist’s most recognizable works.

It’s considered one of his best works since it reflects a famous urban legend from that era.

There is a strong sense of unity between the two sections of this enormous painting, which are approximately divided in half to show the sky and the ground, respectively.

The work has been praised by art historians, who have called it everything from “the epitome of Greco’s artistic style” to “one of the most accurate pages in the history of Spain” and a masterpiece of Western art and of late Mannerism.

5. Volterra Deposition – Rosso Fiorentino

Completed in 1521, Rosso Fiorentino’s The Deposition from the Cross is an altarpiece showing the Deposition of Christ. The artist’s signature and the year the painting was created are both dated and written at the bottom of the canvas: RUBEUS FLOR. A.S. MDXXI.

In most people’s eyes, it’s the artist’s pinnacle work. This oil on wood artwork used to hang in the Volterra Duomo but has since been relocated to the Pinacoteca Comunale.

Pontormo, another Mannerist painter, painted a similar scene on his Deposition canvas in Florence about the same time, in 1528.

For the church of San Lorenzo, Sansepolcro, Rosso painted a second, darker, and more crowded Deposition.

6. The Wedding at Cana – Paolo Veronese

Paolo Veronese’s The Wedding Feast at Cana, based on the biblical story of Jesus turning water into wine, is a realistic depiction of this miracle.

This large-scale oil painting (6.77 m x 9.94 m) was created in the Mannerist style of the late Renaissance (1520-1600) and exemplifies the pursuit of compositional harmony by artists like Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo.

Mannerism was an exaggeration of Renaissance ideals of figure, light, and color that flattened the pictorial space and distorted the human figure as an ideal preconception of the subject, rather than as a realistic representation.

High Renaissance art (1490–1527) emphasized human figures of ideal proportions, balanced composition, and beauty.

Veronese’s The Wedding Feast at Cana creates visual tension between the picture’s elements and thematic instability among the human figures through the use of technical artifice, the inclusion of sophisticated cultural codes, and symbolism (social, religious, and theological), all of which present a biblical story relevant to both Renaissance and modern viewers.

From the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, the painting was displayed in the monastery’s refectory. In 1797, during Napoleon’s French Revolutionary Army’s battles in Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), the picture was stolen as war booty.

The Wedding Feast at Cana is the largest painting in the Musée du Louvre collection due to the sheer size of the canvas (67.29 m2).

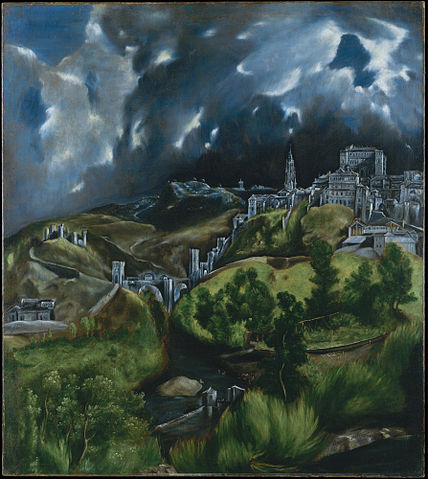

7. View of Toledo – El Greco

View and Plan of Toledo, sometimes referred to as Vista de Toledo, is the other of El Greco’s landscapes that has made it to modern times. A painting titled View of Toledo can be seen in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

View of Toledo is one of the most famous depictions of the sky in Western art, alongside Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night and the landscapes of J.M.W. Turner and Claude Monet.

Many art historians regard the artist’s painting View of Toledo to be a watershed moment in Western art.

Spanish Renaissance and Baroque paintings rarely feature landscapes. As landscape paintings are so unusual, some have speculated that View of Toledo is a cut from a larger piece.

But there hasn’t been any solid proof or confirmation either way. This painting has been considered the first example of Spanish landscape painting because it predates the ban on landscape painting enforced by the Council of Trent.

8. The Feast in the House of Levi – Paolo Veronese

Artist Paolo Veronese spent the majority of his life in Venice, where he was born in the middle of the Italian Renaissance.

His depictions of religious people and events from the Christian New Testament have earned him comparisons to such luminaries of the Renaissance as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.

The Feast in the House of Levi, one of Veronese’s most renowned paintings, was finished in 1573, at a time when other artists were trying to earn prominence by depicting scenes from the Bible.

In spite of the painting’s upbeat depiction of Christ and his followers, it was widely panned when it was initially shown.

For his portrayal of some people in the picture, Veronese was hauled before a trial and faced serious allegations of heresy.

9. The Fall of Man – Titian

The Fall of Man, painted by the Venetian artist Titian circa 1550, depicts the narrative of Adam and Eve and is presently housed in the Prado in Madrid.

Details are based on the print by Albrecht Dürer entitled Adam and Eve and Raphael’s fresco of the same subject at the Vatican’s Stanza della Signatura, both of which feature seated Adam and standing Eve.

Once owned by Philip II of Spain’s secretary Antonio Pérez, and maybe commissioned by his father, the painting entered the Spanish royal collection in 1585, where it remained until Rubens replicated it between 1628 and 1629 for his own rendition of the subject.

10. Miracle of the Slave – Tintoretto

Jacopo Tintoretto, an Italian Renaissance painter, created The Miracle of the Slave (1548), also known as The Miracle of St. Mark, which is currently on display at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. The city confraternity Scuola Grande di San Marco originally commissioned it.

Saint Mark (the patron saint of Venice) is depicted in this scene from the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine. The upper half of the scene depicts the saint saving the life of a slave who is going to be martyred because he worships the relics of another saint. Each character is etched onto a different architectural setting.

Although Tintoretto clearly drew inspiration from Michelangelo, the picture’s rich colors and precise detail are more typical of the Venetian School.