Johannes Vermeer (sometimes spelled Jan Vermeer; October 1632 – December 1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period painter famed for his home interior depictions of middle-class life.

He was a reasonably successful provincial genre painter during his lifetime, acknowledged in Delft and The Hague. Despite this, he made a small number of paintings and was clearly not affluent, leaving his wife and children in debt upon his death.

Vermeer worked slowly and meticulously, usually used very costly pigments and worked almost exclusively in oils. He is especially well-known for his masterful handling and use of light in his paintings.

Almost all of Vermeer’s paintings seem to be set in two smaller rooms of his Delft home; they include the same furniture and decorations in a variety of configurations, and frequently depict the same characters, primarily ladies.

Gustav Friedrich Waagen and Théophile Thoré-Bürger rediscovered Vermeer in the nineteenth century, when they wrote an article attributing 66 paintings to him, however only 34 works are widely credited to him today.

Vermeer’s reputation has increased since then, and he is now widely regarded as one of the best painters of the Dutch Golden Age.

Famous Vermeer Paintings

1. Girl with a Pearl Earring

In 1665, Vermeer created one of the most iconic portraits of all time. The oil painting depicts a young girl staring back at the spectator with an enticing expression that piques the interest of those who have the pleasure of seeing this work.

The work is renowned for its astounding degree of realism and Vermeer’s ability to portray the tiny differences between light and shade.

According to art experts and aficionados, the girl’s eyes are one of the most intriguing aspects of the piece since they are riveted on the observer in a humorous and anticipating manner.

Rather than just displaying her profile to the observer, the young lady looks over her shoulder closely with an almost curious face.

The contrast between light and shadow, as well as the delicate color mixes, contribute to this painting becoming the most famous Vermeer painting.

2. The Art of Painting

The Art of Painting, sometimes referred to as The Allegory of Painting or The Painter at His Studio. It is owned by the Austrian Republic, and it is on exhibit in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum.

This illusionistic masterpiece is one of Vermeer’s most well-known works.

Numerous art historians believe it is an allegory of painting, which explains the picture’s other title. It is the most difficult Vermeer work in terms of composition and iconography. It is Vermeer’s third biggest piece, after Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and The Procuress.

The painting is regarded significant for Vermeer since he refused to part with it or sell it, despite his financial difficulties. On 24 February 1676, his wife Catharina left it to her mother, Maria Thins, in order to prevent the picture being sold to settle creditors.

Until 1860, the picture was attributed to Vermeer’s contemporary, Pieter de Hooch; Vermeer remained relatively unknown until the late nineteenth century.

On the painting, Hooch’s signature was even falsified. It was only when the German art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen intervened that it was identified as a Vermeer original.

3. The Milkmaid

The Milkmaid, sometimes referred to as The Kitchen Maid, is an oil-on-canvas picture depicting a “milkmaid,” who is really a home kitchen maid. It is presently on display in the Netherlands’ Rijksmuseum, which describes it as “unquestionably one of the museum’s best attractions.”

The actual year of completion of the artwork is uncertain, with estimations varied according to source. The Rijksmuseum dates it to about 1658. It was painted in around 1657 or 1658, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The painting implies that the woman is preparing bread pudding, which would explain the milk and broken bread on the table.

By representing the working maid carefully cooking, the artist creates not simply an ordinary image, but one with ethical and societal significance. The modest lady is repurposing everyday items like otherwise worthless stale bread to produce a joyful domestic product.

The painting also has a “classic balance” of figurative components and a “amazing use of light,” which The Metropolitan Museum of Art attributes to Delft craftsmanship and Vermeer’s work.

The wall on the left immediately draws you into the picture—that recession to the left and then the openness to the right—and this kind of left-corner scheme had been utilized for around ten years prior to Vermeer.

4. The Little Street

This painting is one of Vermeer’s very few signed works, making it one of the most expensive paintings remaining in existence. The Little Street is the title of the artwork, which is thought to have been finished in 1657 or 1658.

This picture depicts a rather frank depiction of a serene, calm street that was reportedly a frequent sight in numerous locations around Holland during this time period.

Along with the incredible amount of detail in the painting, critics and academics refer to Vermeer’s use of precise angles and forms to draw the viewer’s attention to specific regions, such as the left side and the narrow alleyway towards the center.

The oil on canvas artwork is 54.3 centimetres (21.4 in) high by 44.0 centimetres (17.3 in) wide and is relatively small in comparison to Vermeer’s paintings.

The artwork, which shows a peaceful street, encapsulates elements of life in a Dutch Golden Age town. Vermeer painted just three views of Delft, the others being View of Delft and the now-lost House Standing in Delft. This painting is regarded as a significant work by the Dutch painter.

Straight angles alternate with the triangles of the house and sky, imparting life to the arrangement. The walls, stones, and bricks are all covered with a deeper paint layer, which gives them an almost tactile quality.

Vermeer accomplished the accurate rendering of the surfaces by the deft use of a small number of colors.

He used red ochre and madder lake to color the reddish-brown brick wall, then lead white and natural ultramarine to color the sky. Azurite combined with lead-tin-yellow is used to paint the green shutters and foliage.

5. Woman Reading a Letter

Woman Reading a Letter, around 1663, has been in the collection of the City of Amsterdam since the Van der Hoop bequest in 1854, and in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam since its opening in 1885, when it was the first Vermeer acquisition.

No part of corner, floor, or ceiling is visible in this picture, which is unusual among Vermeer’s interiors.

The arrangement and figure of the female subject are reminiscent to Vermeer’s 1657–59 painting Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window(below). This piece has a strong resemblance to his contemporaneous Woman with a Pearl Necklace and Woman Holding a Balance(also below).

6. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window was completed between 1657 and 1659 and is now on exhibit in Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie.

For many years, the painting’s attribution was lost, with Rembrandt and subsequently Pieter de Hooch being attributed with the piece until it was officially recognized in 1880 as a Vermeer.

The picture was temporarily in the custody of the Soviet Union after World War II. Tests conducted in 2020 confirmed that the picture had been changed after the painter’s death.

It was one of the artworks spared from destruction during World War II’s bombardment of Dresden. The picture was kept in a tunnel in Saxony among other famous pieces of art; when the Red Army came upon them, they were taken.

The Soviets characterized this as a rescue operation; others saw it as robbery. In any case, upon Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviets chose to return the paintings to Germany.

7. Woman Holding a Balance

Woman Holding a Balance, sometimes titled Woman Testing a Balance, is presently on view at Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art.

The artwork, produced between 1662 and 1663, was originally titled Woman Weighing Gold, but a closer examination revealed that the scale in her hand is empty.

Opinions on the painting’s topic and symbolism vary, with the lady considered as a sign of either holiness or earthliness.

The painting was auctioned as part of a significant collection of Vermeer works from the estate of Jacob Dissius (1653–1695) in Amsterdam on May 16, 1696.

It brought 155 guilders, much more than his Girl Asleep at a Table (62) and The Officer and the Laughing Girl (about 44) garnered at the time, but somewhat less than The Milkmaid.

8. View of Delft

View of Delft is a 1659–1661 oil painting of the Dutch artist’s hometown and is one of his most well-known works, having been made at a period when cityscapes were uncommon.

Along with The Little Street and the lost work House Standing in Delft, it is one of Vermeer’s three known paintings of Delft.

The work’s use of pointillism shows that it predates The Little Street, and the lack of bells in the New Church’s tower places it between 1660 and 1661. Since its inauguration in 1822, the Dutch Royal Cabinet of Paintings at the Mauritshuis in The Hague has housed Vermeer’s View of Delft.

Vermeer is thought to have captured the detail in this picture with the use of an optical device—possibly a camera obscura or a telescope.

9. The Procuress

The Procuress is a 1656 oil on canvas work by Vermeer, who was 24 years old at the time. It is on display in Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister.

It is his first genre painting and depicts a current setting, maybe a scene of mercenary love in a brothel. It stands in stark contrast to his other biblical and mythical settings.

This painting should not be confused with another by the same name by Dirck van Baburen, nor with a fraud originally ascribed to Vermeer, for which technical study in 2011 found the presence of Bakelite in the paint, thus establishing the artwork’s fabrication status.

It was very certainly carried out by the infamous forger Han van Meegeren, who was responsible for multiple forgeries of Vermeers and was known to employ such glue to solidify the paint.

Hermann Kühn conducted a technical examination of this picture in 1968. Vermeer used his customary colors, such as ultramarine in the blue wine jug and lead-tin-yellow in the woman’s clothing, according to the pigment analysis.

Additionally, he used smalt in the green areas of the tablecloth and the greenish backdrop, which is a less often occurrence for him.

10. The Lacemaker

The Lacemaker, created between 1669 and 1670, is now housed in the Louvre in Paris. Depicts a young lady wearing a yellow bodice holding a pair of bobbins in her left hand while carefully inserting a pin into the cushion on which she is creating bobbin lace.

The piece is the tiniest of Vermeer’s paintings, measuring 24.5 cm × 21 cm (9.6 in x 8.3 in), but is also one of the most abstract and peculiar.

The canvas was cut from the same bolt as A Young Woman Seated at the Virginals, and both paintings seem to have started off with similar proportions.

The girl is juxtaposed against a blank wall, most likely to avoid exterior distractions from the core picture. Vermeer most likely employed a camera obscura to compose the work: several optical characteristics, characteristic of photography are visible, most notably the blurring of the foreground.

Vermeer’s use of out-of-focus parts on the canvas enables him to convey depth of field in a way that is rare for Dutch Baroque painting of the period.

11. Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

Vermeer completed Christ in the House of Martha and Mary in 1655. It is presently on display in Edinburgh’s Scottish National Gallery.

It is Vermeer’s biggest painting and one of the few with an overt religious theme. The tale of Christ visiting the two sisters Mary and Martha’s home dates back to the New Testament.

Christ in the House of Mary and Martha is another title for the piece (reversing the last two names)

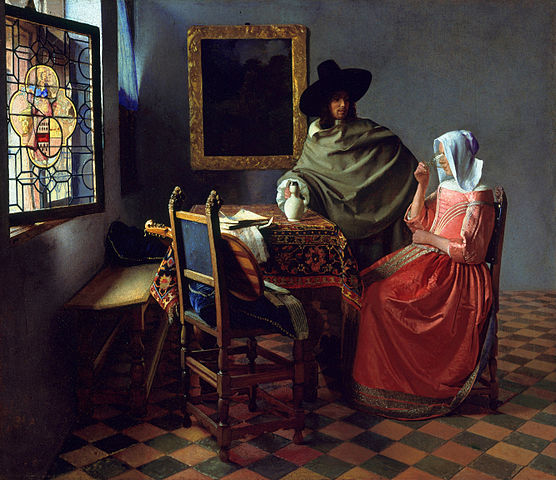

12. The Glass of Wine

The Wine Glass (also known as The Glass of Wine) is a 1660 painting by Johannes Vermeer that is presently housed at Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. It depicts a sitting lady and a standing male drinking in a room.

The piece adheres to the genre painting standards of Pieter de Hooch’s Delft School, which he established in the late 1650s.

It has figures in a brilliantly lighted and expansive interior, and its architectural space is well defined. The people are placed in the middle ground rather than the front.

Vermeer’s brushwork in The Wine Glass is restrained in comparison to his previous works, and the characters’ features and attire are shown with broad smooth edges. Only on the tablecloth tapestry and on the window glass did the artist use extremely precise, linear brush strokes.

The artwork has characteristics that are similar to previous Vermeer works. The Girl with the Wine Glass (1659–1660) depicts two males, but it shares a lady sitting at a table with a glass of wine with The Wine Glass, and the tiled flooring and stained-glass windows in both are quite similar.

The identical wine pitcher may be seen in an older Vermeer painting, A Girl Asleep (1657).

13. The Allegory of Faith

The Allegory of Faith, commonly known as the Allegory of the Catholic Faith, is a 1670–1672 Dutch Golden Age painting by Johannes Vermeer. It has been on display in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art since 1931.

This and Art of Painting are his sole works in the present hierarchy of genres that belong under historical painting, however they retain his traditional composition of one or two characters in a household environment.

Both paintings have numerous characteristics: the viewpoint is almost identical, and there is a multicolored tapestry to the left of each picture, which is dragged to the left to reveal the subject.

The Art of Painting also employs symbolism from the muse of history, Cesare Ripa of Clio. A similar gold panel appears in Vermeer’s Love Letter. The Allegory and The Art of Painting are stylistically and conceptually distinct from Vermeer’s other artworks.