Australia’s magnificent landscapes have inspired artists of many types, from traditional aboriginal iconography to the first European settlers.

Examples include Aboriginal, Colonial, Landscape, Atelier, early-twentieth-century painters, printmakers, photographers, and sculptors influenced by European modernism, and contemporary art.

The visual arts have a long history in Australia, with evidence of Aboriginal painting dating back at least 30,000 years.

Australian painting can be divided between the traditional aboriginal art forms and that of the European settlers which were heavily influenced by both the realism and impressionism art movements.

Famous Australian Paintings

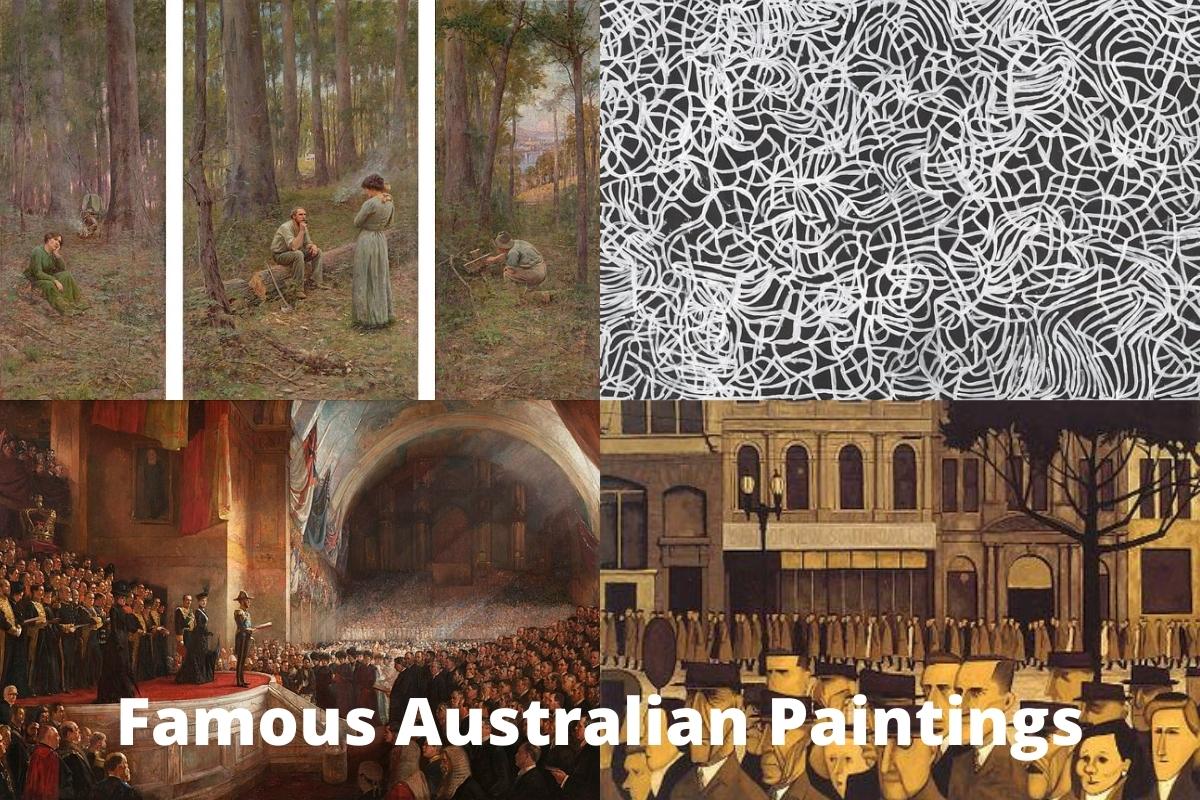

1. The Pioneer – Frederick McCubbin

Frederick McCubbin painted The Pioneer in 1904. The picture is a triptych, with three panels telling the narrative of a free selector and his family trying to make a living in the Australian wilderness. It is generally regarded as one of Australia’s masterpieces.

The artwork is part of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Australian art collection and is on display in the Ian Potter Centre in Melbourne’s Federation Square.

The triptych’s three panels describe the narrative of a free selector, a farmer who has selected some land to clear and cultivate, and his family.

The narrative is unclear, like are many of McCubbin’s previous works, and McCubbin opted not to reply when debate erupted about the “right” interpretation.

The left panel depicts the selector and his wife making their decision; the lady in the forefront is immersed in thinking. The infant in the woman’s arms in the middle panel suggests that some time has passed.

In a clearing in the woods, a cottage, the family home, can be seen. The right panel depicts a guy hunched over a grave. A city may be seen in the backdrop, showing that time has passed.

It’s unknown whose grave it is or whether the guy is the pioneer, the infant from the middle panel, or a stranger who happened across the tomb.

A close examination of the painting’s materials and method found that, to create “luminosity and texture,” McCubbin applied a second coat of lead white to the ground in the middle panel; the brush traces in the firmer lead white can be seen through the subsequent layers in raking light.

Raking light also reveals that a palette knife was used to add paint to the surface in several locations. The picture is still in its original frame, which may have been resurfaced.

Michael Varcoe-Cocks, the National Gallery of Victoria’s director of conservation, spotted a shadow of an unusual form on the surface of the central panel when investigating the painting by torchlight in November 2020.

The artist had painted over his earlier 1892 piece, “Found,” which featured a life-size bushman clutching a little kid, according to X-Rays of the painting and a small black-and-white image contained in McCubbin’s scrapbook.

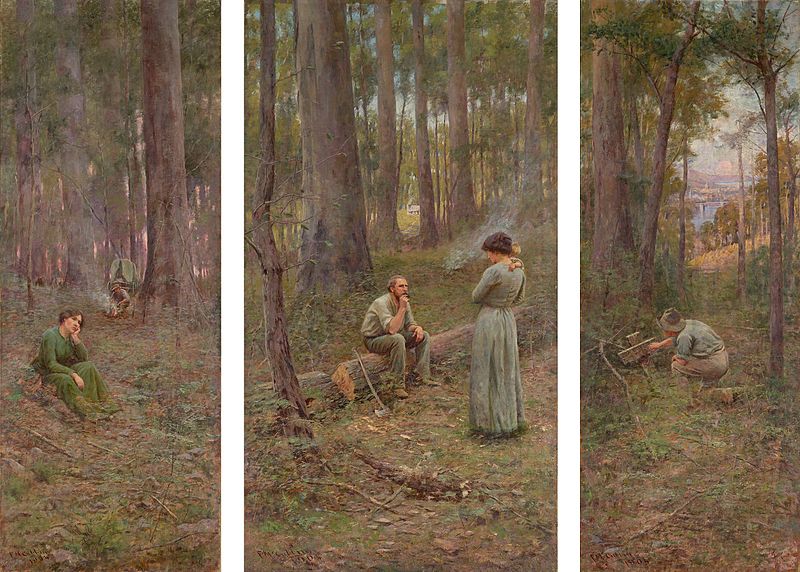

2. Down on His Luck – Frederick McCubbin

Down on His Luck is a painting by Australian artist Frederick McCubbin from 1889. It portrays a disappointed swagman sitting beside a campfire in the middle of nowhere, bitterly musing over his misfortune.

According to a review published in 1889, “The expression betrays difficulties, acute and blighting in their power, yet there is a careless and somewhat sarcastic attitude that announces the lack of any self-pity… McCubbin’s film has a very Australian feel about it.” The surrounding bush is painted in dark tones to depict his solemn and reflective demeanor.

Louis Abrahams, the artist’s model, was a friend and prominent tobacconist in Melbourne who had previously provided the cigar box lids for the renowned 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition.

The setting was set at the Box Hill artists’ camp outside Melbourne, although McCubbin is likely to have done further studies of Abrahams in the studio.

William Fergusson held the picture until it was bought by the Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth in 1896.

3. The Big Picture – Tom Roberts

The Opening of the First Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia by H.R.H. The Duke of Cornwall and York (later H.M. King George V), May 9, 1901, is a 1903 painting by Australian artist Tom Roberts, also known as The Big Picture.

The artwork, which measures 304.5 by 509.2 cm (119.9 in 200.5 in), or nearly 10 by 17 feet, shows the inauguration of Australia’s first Parliament on May 9, 1901, at the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne.

The picture is part of the Royal Collection, however it has been on permanent loan to the Australian Parliament since 1957. Andrew Mackenzie describes the piece, which is presently on display at Parliament House in Canberra, as “…undoubtedly the major work of art chronicling Australia’s Parliamentary History.”

After decades of arguments and negotiations, the colonies on the Australian continent created a federation on July 31, 1900.

While the new Australian Constitution called for a new capital to be built distant from the main cities, Melbourne was selected as the interim seat of government.

Elections were conducted for the first Australian Parliament, and on May 9, 1901, the new parliament was sworn in in Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Building.

The inauguration of the new parliament was seen as a historic and important event, with King Edward VII’s son, the Duke of Cornwall and York (later George V), visiting Australia to formally inaugurate the new parliament on behalf of the King.

The “Australian Art Association,” a syndicate of wealthy donors, intended to commission a painting of the event as a “present to the country” to suitably commemorate the moment.

The consortium’s motivations were not wholly altruistic; they planned to benefit from the sale of prints. Roberts was not the consortium’s first option, with J. C. Waite being selected originally.

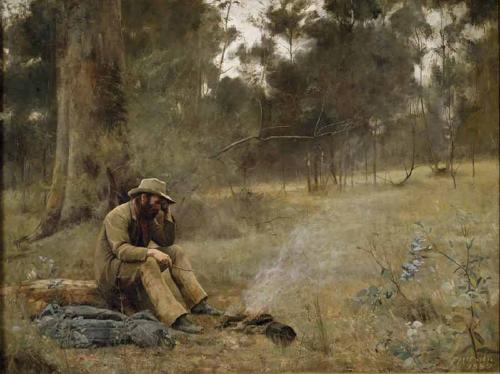

4. The Sunny South – Tom Roberts

The Sunny South is a painting by Australian artist Tom Roberts from 1887. The artwork portrays a group of nude lads swimming at Ricketts Point in Beaumaris, Victoria, a Melbourne suburb.

The National Gallery of Victoria purchased the picture in 1940 with monies from the Felton Bequest.

The title seems to have three meanings. The title relates to the classic production The Sunny South, which was initially performed in Melbourne by George Darrell and starred Essie Jenyns in 1883, four years before the picture was completed, and then transported to London.

Ricketts Point, Beaumaris, is a beachfront neighborhood to the south of Melbourne that is very popular in the summer. The third allusion might be to the uncovered rear of the painting’s primary subject.

5. The Sock Knitter – Grace Cossington Smith

Grace Cossington Smith, an Australian artist, painted The Sock Knitter in 1915. The picture portrays a lady knitting a sock, which is thought to represent the artist’s sister. It was Cossington Smith’s first work to be displayed, and it has been “regarded as the first post-impressionist painting to be exhibited in Australia.”

The figure is pushed forward onto the image plane. Constructed with care. The background’s creamy impasto paint binds the image together. The backdrop is then held together by the sitter. Like a jigsaw puzzle. She is the one who creates the patterns. There are echoes of triangles all throughout the place.

In 2015, the painting was exhibited in the Follow the Flag exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. The Sock Knitter “has come to represent Australian women’s participation to the [First World War] effort, which included knitting more than 1.3 million pairs of socks,” according to exhibition materials.

In 1960, the artwork was purchased by the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

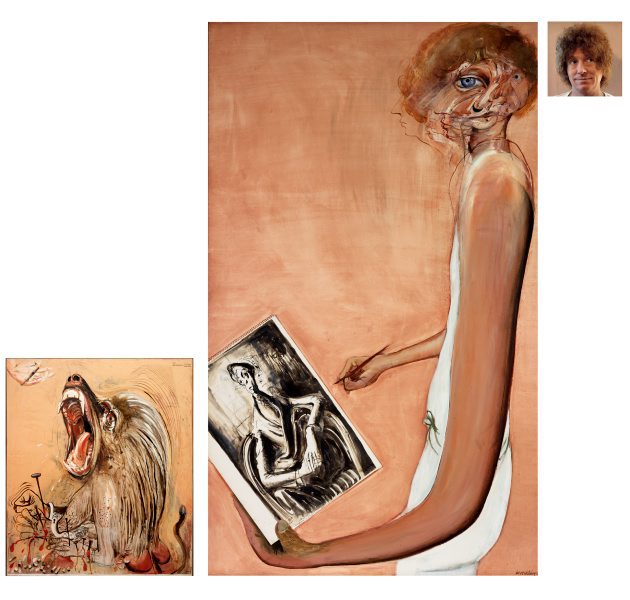

6. Art, Life and the other thing – Brett Whiteley

Art, Life, and the Other Thing is a triptych painting by Australian artist Brett Whiteley that was awarded the Archibald Prize in 1978.

Brett Whiteley himself is shown on the central canvas, standing side on to the spectator, his head moving and his hands grabbing. A black-and-white depiction of Joshua Smith by William Dobell with one hand, a paint brush in the other, while he paints this portrait.

His body flows vertically to the canvas, leaving the left side practically vacant. The figure’s features are confused and exaggerated, particularly in the head, where Whiteley is moving. The head seems quite abstract as a result of this movement.

The arms, legs, and torso are all much too long and lanky. The body is dressed in a two-piece white attire. As the head rotates, it gets more genuine and substantial, transitioning from a jumble of fuzzy lines on the left to almost photo-realistic on the right.

To add to the authenticity, Whiteley had placed his own hair to the right-hand side piece. The backdrop is a soft orange color.

The triptych concludes with a tiny portrait of Brett Whiteley himself. It is the tiniest component and is located on the far right, at the top-left corner of the piece. The image is cropped just below Whiteley’s chin.

The person is smiling and has a contemplative look on his face, and his gaze is drawn to someplace beyond the spectator, to our right (his left). His hair appears unkempt, indicating that this is not an official shot. The backdrop is a soft orange color.

The triptych’s left side is a medium-sized oil painting on canvas done in warm, earthy hues including browns, oranges, yellows, and reds.

It portrays a crazy baboon, imprisoned and chained, with cuts and wounds inflicted by nails piercing its hands and wrists. The baboon is visibly in action, battling the excruciating agony and suffering. It has crazy eyes and a gaping mouth.

The baboon takes up the most of the artwork, however it is not a true-to-life/realistic painting, but rather one that has been warped to emphasize its attributes. A hand, palm extended, is holding out a syringe to the baboon in the upper left-hand corner. The hands of the baboon are human. Nothing can be seen in the backdrop.

At the time, this portion was arguably the most illuminating about Brett Whiteley’s life. The distressed baboon represents his fight with drug addiction, namely heroin. The nails on its hands and the furious desperation of the creature’s canvas are the biggest in size in this section.

7. Golden Summer, Eaglemont – Arthur Streeton

Arthur Streeton created the landscape picture Golden Summer, Eaglemont in 1889. It is an exquisite portrayal of bright, undulating plains that reach from Streeton’s Eaglemont “artists’ camp” to the distant blue Dandenong Ranges outside Melbourne, painted en plein air at the height of a summer drought.

It is a classic example of the artist’s unique, high-keyed blue and gold palette, which he called “nature’s scheme of color in Australia.” It is naturalistic but lyrical, and a purposeful attempt by the 21-year-old Streeton to produce his largest work yet.

The picture was purchased by the National Gallery of Australia in 1995 for $3.5 million, a record price for an Australian painting at the time. It is still regarded a classic of Australian Impressionism and one of Streeton’s most renowned works.

Streeton created the piece en plein air in January 1889 at his Eaglemont “artists’ camp” in Heidelberg, a then-rural neighborhood on Melbourne’s outskirts.

In late 1888, he travelled through the region in quest of the location featured in one of his favorite paintings, Louis Buvelot’s Summer Afternoon, Templestowe (1866).

The picture is notable for its heavy coating of paint, and Streeton approached the canvas with a knife one evening in the Eaglemont homestead in order to scrape away some of the layers. Streeton was afterwards grateful to Roberts for convincing him to “leave it alone.”

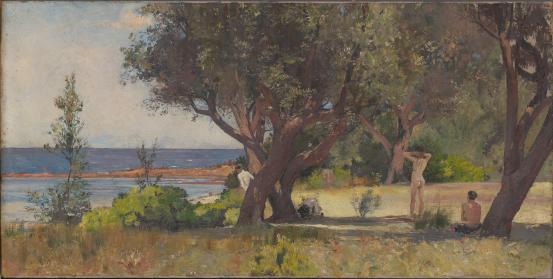

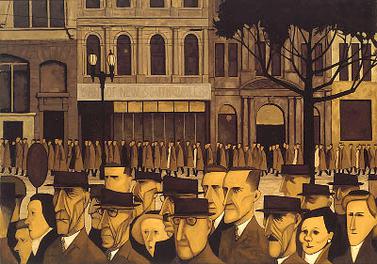

8. Collins St., 5 pm – John Brack

Collins St., 5 p.m. is a painting by Australian artist John Brack from 1955. The artwork shows office employees wandering along Melbourne’s popular Collins Street after ending their day’s work—”Blank-faced office workers speed past like sleep-walkers, thinking only of the bars or their homes in the suburbs.”

Brack was inspired to create the piece after reading T. S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land. It is regarded as a companion piece to Brack’s previous work The Bar.

The artwork was bought from Peter Bray Gallery for the National Gallery of Victoria’s permanent Australian art collection and is now on display in the Ian Potter Center in Melbourne’s Federation Square.

Collins St., 5 p.m. was chosen the most popular piece in the National Gallery of Victoria’s collection in 2011.

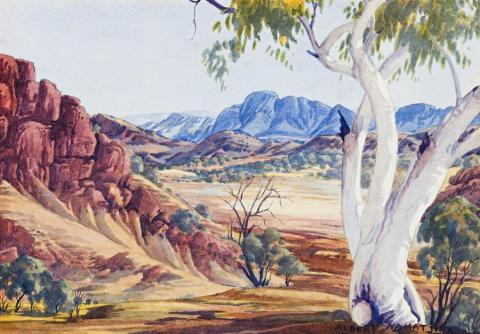

9. Central Australian Landscape – Albert Namatjira

Namatjira’s artworks depicted the Australian environment in a colorful and diversified manner. Central Australian Landscape, one of his early landscapes from 1936, depicts a country of rolling green hills.

In 1934, Namatjira was attracted to western-style painting via an exhibition at his mission by two artists from Melbourne, Rex Battarbee and John Gardner.

Also Read: Famous Aboriginal Artists

In the winter of 1936, Battarbee went to the region to paint the scenery, and Namatjira, who shown an interest in learning to paint, functioned as his cameleer and guide, showing him local picturesque locations. Battarbee demonstrated watercolor painting to him.

Namatjira began painting in his own distinctive style. His landscapes often emphasized both the land’s harsh geological characteristics in the backdrop and the unique Australian flora in the foreground, with extremely ancient, stately, and magnificent white gum trees surrounded by twisted bush.

His painting featured a great level of light, displaying the land’s gashes and the bends in the trees. His hues were comparable to the ochres used by his forefathers to represent the same environment, but his approach was admired by Europeans since it adhered to the ideals of western art.

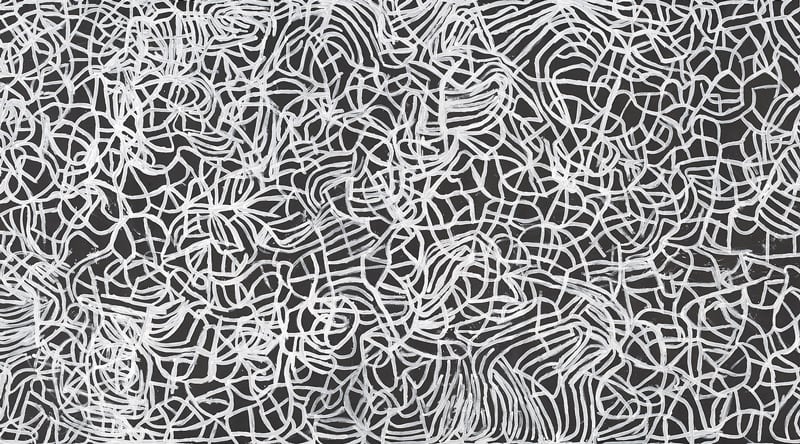

10. Big Yam dreaming – Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Measuring a whopping three by nine meters Big Yam Dreaming was created by Emily Kame Kngwarreye over a two day period.

She had the canvas primed by her assistants in black, once dry she then sat on the cavas and completed the work.

It was completed towards the end of her career and was in contrast to her much brighter dot paintings that she produced in her earlier.

Kngwarreye’s works often included yam tracks. The yam plant was an essential source of sustenance for the desert’s Aboriginal inhabitants.

She painted several pieces on this topic, and the yam tracking lines were often her first moves at the start of a painting.

This plant was particularly meaningful to her since her middle name, Kame, refers to the golden bloom of the yam that grows above ground. Her drawings, she said, have significance based on many parts of the community’s existence, including the yam plants.