Many outstanding sculptures by some of the world’s most renowned artists may be seen in Italy.

Many iconic masterpieces may be seen in practically every square or piazza in almost every major town and city around the nation.

When traveling across Italy, remember to look up since many sculptures stand proudly on top of the buildings.

When it comes to its various contributions to the realm of art, the Italian Renaissance is regarded as one of history’s most important epochs.

Sculptors would push the art form to new heights of realism by studying anatomy for thousands of hours and applying it precisely with hammer and chisel.

The great Italian artists created sculptures and statues not seen since the early Greek and Roman periods.

To produce these magnificent sculptures and monuments, the sculptors dedicated themselves to lifelong learning and a never-ending pursuit of excellence.

Famous Italian Sculptures

1. David – Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was a notable figure during the Italian Renaissance, which lasted from the 15th through the 16th century. Michelangelo was well recognized as a painter, but it was his sculpting that captured the attention of everyone who observed his work.

Michelangelo’s finest sculpture, according to critics and history, is his work known as David. The artist created this larger-than-life monument of the well-known Biblical king and hero in 1504.

Michelangelo was commissioned to create the piece by the city of Florence, Italy, where he had previously created a number of renowned sculptures.

The sculpture was originally supposed to be placed along the roof-line in front of the city’s cathedral, but when completed, it was judged too stunning to be retained at that distance.

Rather than that, the sculpture was erected in front of the city’s headquarters, the Palazzo Vecchio. The masterpiece, which was carved from marble, is regarded as one of the most realistic portrayals ever created.

2. David Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss – Antonio Canova

Psyche Resurrected by Cupid’s Kiss is a 1787 sculpture by Antonio Canova commissioned by Colonel John Campbell.

It is regarded as a Neoclassical sculpture masterpiece, yet it represents the mythical lovers in a moment of extreme desire, which was typical of the rising Romantic style.

It represents the god Cupid at his most loving and compassionate, immediately after kissing the dead Psyche to bring her back to life. The fable of Cupid and Psyche, based on Lucius Apuleius’ Latin classic The Golden Ass, is well-known in art.

Joachim Murat acquired the first or prime version in 1800. (shown). In 1824, after his death, the statue was presented to the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.

The second version of the sculpture was acquired by Prince Yusupov, a Russian prince, from Canova in Rome in 1796, and it was subsequently transferred to the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. A full-scale reproduction of the second edition may be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

3. The Pietà – Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, better known as Michelangelo, was one of the finest painters of the Italian Renaissance. He was an accomplished painter, but most art historians and critics regard him as one of the best sculptors of all time.

He created a number of masterpieces that grace the halls of Rome’s churches, as well as those of other important Italian towns.

One of his most famous sculptures is simply referred to as Pietà. Completed in 1499, this magnificent statue represents Mary, Jesus’ mother, holding her son’s dying corpse in her arms.

The sculpture was initially planned as a memorial for Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, the French envoy to Rome. However, once finished, the sculpture was judged too spectacular to be shown just as a burial piece and was instead installed in Vatican City’s St. Peter’s Basilica.

Perhaps the most recognized aspect of the sculpture is Michelangelo’s ability to convey detailed detail. Everything from Jesus’ hands to Mary’s face, and particularly her dress and robes, is done with remarkable, realistic realism.

4. David – Donatello

Another statue of the Biblical character David was created by Donato di Niccol di Betto Bardi, a notable Renaissance artist. Known simply as Donatello, the artist was a pivotal character throughout his time period.

This depiction, in stark contrast to Michelangelo’s, depicts the legendary Bible hero and monster slayer as a youthful, thin lad.

The bronze statue is often referred to as The Bronze David due to its creation around the same time period as Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

Completed around the 1440’s, David is oddly shown sporting a hat type that was popular among Italian aristocracy throughout the Renaissance period.

He is pictured resting on one leg while wielding a sword that he has pointed into the ground. At David’s feet is King Saul’s armor. This bronze sculpture is regarded to be one of the most perfectly proportioned ever produced.

5. Madonnina – Carlo Pellicani

The Madonnina is a Virgin Mary statue that stands atop Milan Cathedral in Italy.

The Madonnina spire, also known as the guglia del tiburio (“lantern spire”), was built in 1762 at a height of 108.5 m (356 ft), as planned by Francesco Croce.

The polychrome Madonnina statue, which stands atop the spire, was created and constructed by Carlo Pellicani in 1774, under the episcopacy of Giuseppe Pozzobonelli, who supported the idea of placing the Madonnina atop the Cathedral.

No structure in Milan is taller than the Madonnina, according to tradition. A smaller duplicate of the Madonnina was put atop Gio Ponti’s Pirelli Building in the late 1950s, at a height of 127.1 m (417 ft), therefore the new Madonnina remains the highest point in Milan.

Another copy was installed on the top of the Palazzo Lombardia in 2010, at a height of 161 m (528 ft), making it the highest structure in the city at the time. In 2015, another duplicate was installed atop the Allianz Tower, ensuring that the Madonnina retains the city’s tallest roof, now standing at 209 meters (686 ft).

O mia beautiful Madonnina, the most traditional Milanese ballad, is about the Madonnina. The Derby della Madonnina, as the name suggests, is a local rivalry between the city’s two football teams, A.C. Milan and Inter Milan.

6. Veiled Christ – Giuseppe Sanmartino

The Veiled Christ is a 1753 marble sculpture by Giuseppe Sanmartino that is housed at Naples, Italy’s Cappella Sansevero.

The Veiled Christ is regarded as one of the world’s most extraordinary sculptures and is said to have been made by alchemy. Sculptor Antonio Canova, who attempted to purchase the sculpture, said that he would gladly give up 10 years of his life to create a comparable masterpiece.

The sculptor Antonio Corradini, who specialized in shrouded sculptures, was initially tasked with creating Christ. Corradini, on the other hand, died a short time afterwards, having only made a clay bozzetto (today displayed at the Museo Nazionale di San Martino).

Giuseppe Sanmartino was given the task of creating “a marble statue sculpted with the utmost realism, showing Our Lord Jesus Christ in death, wrapped with a translucent shroud cut from the same block of stone as the statue.”

Sanmartino created a piece in which the dead Christ is lying on a sofa, wrapped by a veil that exactly fits his figure. The skill of the Neapolitan sculptor rests in his effective representation, via the curtain, of Christ’s anguish during the crucifixion. Jesus’ face and torso bear evidence of his anguish.

Sanmartino has carved images of the implements of the passion at Jesus’ feet, adding extra detail to the marble block: pliers, chains, and the crown of thorns.

The sculptor’s masterful representation of the veil has been the subject of a tale, in which the original commissioner, the famed scientist and alchemist Raimondo di Sangro, shows the sculptor how to change linen into crystalline marble.

Many visitors to the Cappella, awestruck by the shrouded artwork, mistakenly assumed it was the product of an alchemical “marblification” done by the prince over the years. He was supposed to have draped a genuine veil over the sculpture and, via a chemical procedure, converted it into marble over time.

Of truth, a thorough examination reveals that the sculpture was fully created in marble. This is also supported by letters sent at the time of its creation. A payment receipt to Sanmartino, dated 16 December 1752 and signed by the prince, is kept in the Bank of Naples’ Historical archive.

7. San Carlone – Crespi

The San Carlone, also known as Sancarlone or the Colossus of San Carlo Borromeo, is a large copper monument located in Arona, Italy, that was created between 1614 and 1698. It is a representation of Charles Borromeo, a Catholic saint and former Archbishop of Milan.

It is situated on a hill overlooking Lago Maggiore, close to the Borromeo family’s historic castle. A succession of chapels were to be built to commemorate the saint’s life, establishing a Sacro Monte for religious meditation and reverence. Only three were constructed in the end.

Giovan Battista Crespi (known as Il Cerano) sculpted the statue, which was built by Siro Zanella of Pavia and Bernardo Falconi of Lugano. It began in 1614, shortly after St Charles Borromeo was canonized.

The 23.5-metre monument is completed with hammered copper panels and bolted together. It is 11.5 meters tall on a granite pedestal. The inside is accessible through tiny steps and ladders, letting guests to see through the eyes and ears.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the French artist who sculpted the Monument of Liberty, stopped in Arona on his way back from Egypt in 1869 to examine the construction of the statue. The Arona colossus is listed on the inscription at the foot of the Statue of Liberty.

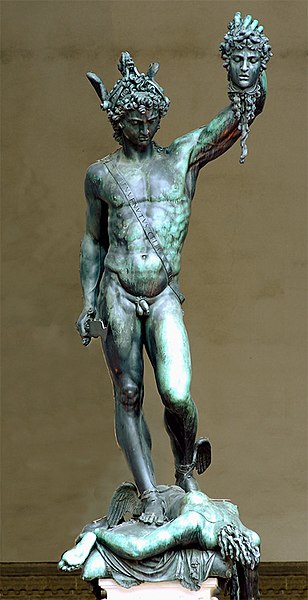

8. Perseus with the Head of Medusa – Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini created the bronze sculpture Perseus with the Head of Medusa between 1545 and 1554. Similar to a predella of an altarpiece, the sculpture rests on a square base with bronze relief panels telling the narrative of Perseus and Andromeda.

It is situated in Florence, Italy, in the Loggia dei Lanzi on the Piazza della Signoria. Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, the second Florentine duke, commissioned the piece, which has unique political ties to the other sculptural works in the plaza.

When the work was shown to the public on April 27, 1554, Michelangelo’s David, Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus, and Donatello’s Judith and Holofernes were already in place.

The ancient narrative of Perseus killing Medusa, a monstrous woman-faced Gorgon whose hair had been changed to snakes; everyone who gazed at her was turned to stone, is the subject of the piece.

Perseus stands victorious, nude save for a sash and winged sandals, on top of Medusa’s body, holding her head, adorned with writhing snakes, in his outstretched hand. Medusa’s severed neck spits blood.

The bronze sculpture depicting Medusa’s head turning men to stone is encircled by three massive marble sculptures of men: Hercules, David, and, later, Neptune.

Cellini’s use of bronze in Perseus and Medusa’s head, as well as the themes he utilized to react to the existing sculpture in the plaza, were very inventive. When seen from the rear, a self-portrait of the sculptor Cellini may be seen on the back of Perseus’ helmet.

The sculpture is regarded to be the first since the classical period in which the base incorporated a figurative sculpture that was an important element of the piece.

9. Hercules and Cacus – Bandinelli

Hercules and Cacus is a white sculpture located to the right of the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria.

This work by Florentine artist Baccio Bandinelli (1525–1534) was commissioned as a companion piece to Michelangelo’s David, which had been commissioned by the republican council of Florence, led by Piero Soderini, to mark the Medici’s defeat.

The colossus (height: 5.05 m) was donated to the Medici family to accompany the David, but it was eventually taken by Michelangelo as a symbol of his newfound authority following his return from exile in 1512, and again in 1530.

Although records of its presentation in 1534 included vocal and written complaints of the marble, the majority were directed at the Medici family for collapsing the Republic and were not artistic in nature.

Alessandro de’ Medici imprisoned a few of the authors of these hypercritical lyrics, implying a political remark. Giorgio Vasari and Benvenuto Cellini, both supporters of Michelangelo and competitors for Medici patronage, were the two fiercest criticisms.

Vasari bemoaned the transfer of ownership from Michelangelo to Bandinelli, as well as the change in design. Cellini derisively referred to Michelangelo’s emphatic musculature as “a bag full of melons,” forgetting that Leonardo da Vinci had previously derisively referred to Michelangelo.

Because of their rivalry, neither Vasari nor Cellini can be regarded as objective authorities. The patrons (Medici family) were very pleased and paid Bandinelli significantly for his efforts with land and money, and he was eventually appointed in control of all Medici sculptural and architectural works under Cosimo I.

10. Apollo and Daphne – Bernini

Gian Lorenzo Bernini created Apollo and Daphne, a life-sized Baroque marble sculpture, between 1622 and 1625. The piece, which is housed in Rome’s Galleria Borghese, shows the finale of Ovid’s Metamorphoses’ narrative of Apollo and Daphne (Phoebus and Daphne).

The sculpture was the last in a series of commissions given to Bernini by Cardinal Scipione Borghese early in his career.

Apollo and Daphne was commissioned after Borghese had gifted Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi an earlier piece of his patronage, Bernini’s The Rapture of Proserpina.

Much of the early work was completed in 1622–23, but a halt, perhaps to work on Bernini’s David sculpture, prevented its completion, and Bernini did not complete the work until 1625.

The artwork was not relocated to Cardinal Borghese’s Villa Borghese until September 1625. Bernini did not complete the sculpture alone; he worked with a member of his workshop, Giuliano Finelli, who sculpted the elements that indicate Daphne’s transformation from person to tree, such as the bark and branches, as well as her windswept hair.

Some historians, however, see Finelli’s contribution as insignificant. Apollo and Daphne was eventually finished in the autumn of 1625, and it received an instant favorable response.