Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born in Italy in 1475 and is widely recognized as one of the three most influential people in the Italian Renaissance period. He is best known for his sculptures and paintings.

He is better known by his given name, Michelangelo, and many art historians and critics consider him to be the ideal Renaissance man because of his outstanding paintings, architectural achievements, sculptures, and literary works.

During his youth and early childhood, Michelangelo had the opportunity to learn from some of the most illustrious geniuses of the early Renaissance era.

He conducted extensive study into the human form, including dissecting human cadavers to get a better grasp of anatomy, which many historians think was one of the reasons he was able to make sculptures that were extremely realistic in their depiction of the human form.

Michelangelo’s Pieta and David, along with a few other sculptures, are widely recognized as some of the most important pieces of art ever produced in history.

Most people are familiar with him from his work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, but he also produced other notable works during his career. Michelangelo’s David is widely recognized as one of the world’s greatest sculptures of all time.

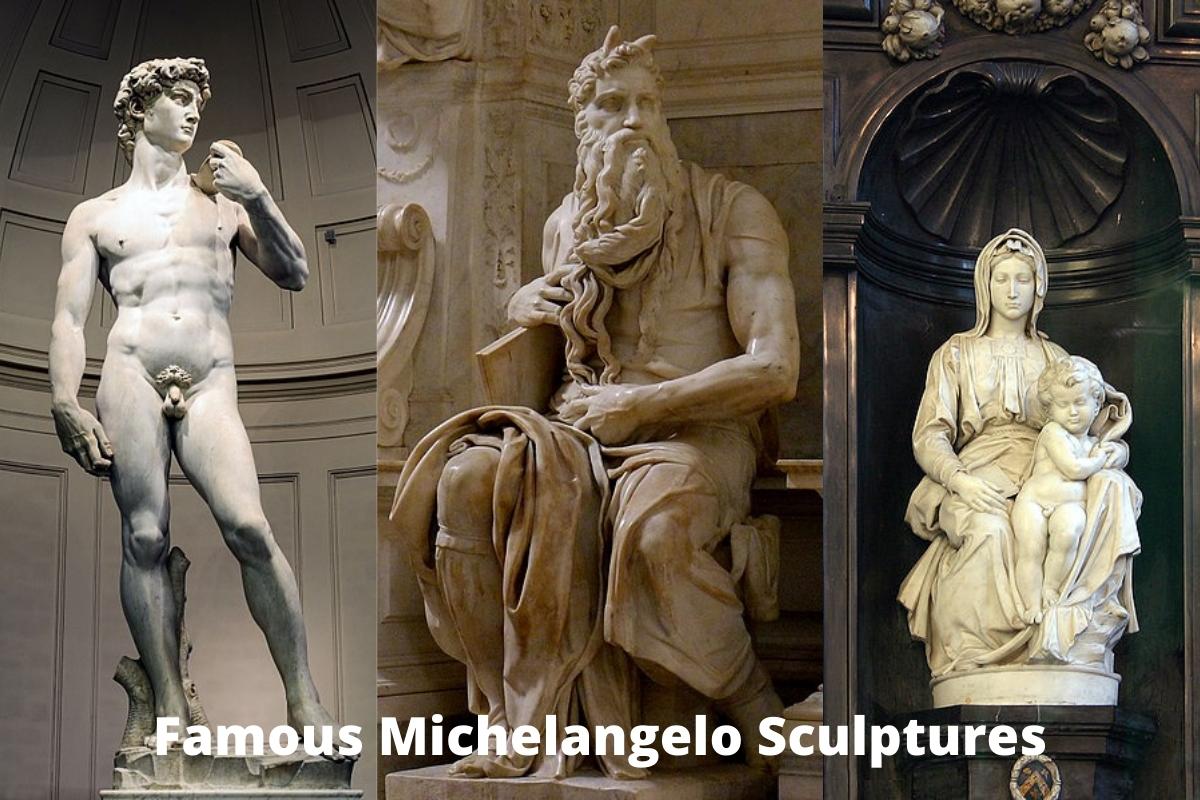

Famous Michelangelo Sculptures

1. David

Michelangelo was a well-known person during the Italian Renaissance period. He was a prolific painter, but he is most known for his skills as a sculptor throughout the 15th and 16th centuries.

Many of his works may be seen in churches and museums across his hometown of Florence, Italy, but one sculpture in particular is one of the world’s most recognized.

The statue, simply titled David, measures 17 feet tall and is larger-than-life. The gigantic marble sculpture was built by Michelangelo in his youth, before he reached the age of thirty.

Also Read: Different Types of Sculptures

The naked picture of David has a muscular body, which was a sign of health and purity for members of the Catholic religion at the time the statue was built. However, many critics and historians feel the monument reflects a deeper significance.

The David statue is also supposed to be a symbol of liberty for the Republic of Florence, which was under attack from the strong Medici family of Rome during this time period. The monument stood in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, which served as Florence’s administrative headquarters in 1504.

He was positioned with his gaze focused on Rome, in what many think was a warning to the Medici dynasty not to seek to exert power in Florence.

2. The Pietà

While Michelangelo is arguably better recognized for his later works, such as the David statue and the Sistine Chapel works, the Pieta sculpture established him as an artist early in his career.

During his tenure with the Medici, Michelangelo carved a number of minor statues in Florence, but in the 1490s, he left Florence for Venice, Bologna, and eventually Rome, where he stayed from 1496 until 1501.

A cardinal named Jean de Billheres commissioned Michelangelo to create a sculpture for a side chapel in Rome’s Old St. Peter’s Basilica. The final piece, the Pieta, would be so popular that it would rocket Michelangelo’s career in ways that no previous work he had done before.

It is the only signed work of Michelangelo. It is also the only Renaissance sculpture known to have been allowed by the Chapter of St. Peter and installed in St. Peter’s Basilica.

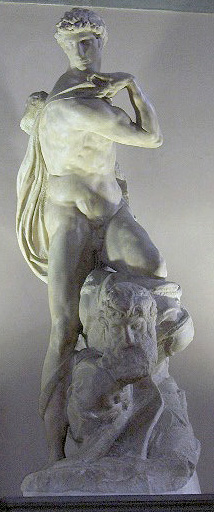

3. Bacchus

The sculpture represents Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and drunkenness, holding a glass and grapes in his hands, with a faun, half man, half goat, standing behind him and devouring the grapes.

It was commissioned by Raffaele Riario, a high-ranking Cardinal and antique sculpture collector, but he declined, and it was finally purchased by Jacopo Galli, Riario’s banker and Michelangelo’s friend.

Along with the Pietà, the Bacchus is one of just two surviving sculptures from the artist’s initial time of stay in Rome.

The Medici bought the statue and transferred it to Florence in 1572.

4. Moses

Moses is a sculpture at Rome’s San Pietro in Vincoli church. It depicts the biblical figure Moses with horns on his head and was commissioned for Pope Julius II’s burial tomb in 1505 and completed in 1545.

When Michelangelo finished sculpting David, it was clear that he had created the most magnificent figure ever, maybe exceeding the beauty of Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures. When Pope Julius II learned about David, he asked Michelangelo to work for him in Rome.

Also Read: Famous Michelangelo Works

Julius II died in 1513, and Michelangelo’s original proposal included approximately 40 statues. The Moses statue would have been placed on a tier about 12 feet 3 inches high, facing a St. Paul figure.

The statue of Moses is placed in the center of the lowest deck in the final design, since the project’s scope was significantly decreased after the Pope’s death.

5. The Madonna of Bruges

Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges is a marble sculpture of the Virgin and Child.

The sculpture is particularly notable for being Michelangelo’s first to leave Italy during his lifetime. Giovanni and Alessandro Moscheroni, wealthy textile merchants in Bruges, long one of Europe’s leading economic hubs, bought it.

Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child, constructed in Italy and sent to Belgium in 1504, is unlike any other depiction. It depicts a mother who is upset by what will happen to her son, rather than a loving and caring mother staring at her child.

The movement of the drapery and the chiaroscuro effect are reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Pietà, which was completed shortly before Madonna and Child. Mary’s long, oval face is reminiscent of the Pietà.

During the French Revolution and World War II, forces stole and hid Michelangelo’s Madonna; it was later recovered and restored to Belgium, where it currently rests in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, Belgium.

6. The Deposition (The Florentine Pietà)

The Deposition (also known as the Bandini Pietà or The Lamentation over the Dead Christ) is a marble sculpture by Michelangelo, the Italian High Renaissance maestro.

Michelangelo created on the sculpture between 1547 and 1555, and it portrays four figures: the dead corpse of Jesus Christ, just carried down from the Cross, Nicodemus (or maybe Joseph of Arimathea), Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary.

Because the sculpture is displayed in Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, it is also known as the Florentine Pietà.

According to Vasari, Michelangelo created the sculpture to adorn his grave in Rome’s Santa Maria Maggiore.

He eventually sold it, however, before the job was completed, after purposefully injuring Christ’s left arm and leg and deleting numerous components for reasons that are still being debated.

Some scholars think it was due to flaws in the marble, which prevented the sculpture from being finished without the addition of a piece of marble from another block (“piecing”).

Vasari said that Michelangelo started working on the sculpture when he was 72 years old. Michelangelo toiled diligently into the night, without commission, using just a solitary light to illuminate his work.

Vasari said that he started working on this sculpture to entertain his thoughts and maintain his body fit. After 8 years of labor, Michelangelo would go on to try to destroy the work in a fit of rage.

This marked the conclusion of Michelangelo’s work on the sculptural group, which passed into the hands of Francesco Bandini, who engaged Tiberio Calcagni, an apprentice sculptor, to restore the piece to its present composition.

Christ’s left leg is missing. The artwork has been plagued with ambiguities and never-ending interpretations from its conception, with no simple explanations accessible.

The face of Nicodemus beneath the hood is thought to be a self-portrait of Michelangelo.

7. Tomb of Pope Julius II

The Tomb of Pope Julius II is a sculptural and architectural ensemble designed by Michelangelo and his collaborators that was commissioned in 1505 but not finished until 1545 on a considerably smaller scale.

Originally designed for St. Peter’s Basilica, the edifice was relocated following the pope’s death to the church of San Pietro in Vincoli on the Esquiline in Rome.

This church was frequented by the Della Rovere family, from whom Julius was descended, and he had served as titular cardinal there. Julius II, on the other hand, is buried with his uncle Sixtus IV in St. Peter’s Basilica, hence the finished construction does not serve as a tomb.

Adriano Marinazzo’s hypothetical recreation of the initial idea for Julius II’s mausoleum (1505). (2018).

The tomb, as originally planned, would have been a massive edifice that would have provided Michelangelo with the space he required for his superhuman, tragic figures.

This project became one of Michelangelo’s greatest disappointments when the pope, for unknown reasons, halted the commission, presumably because funding needed to be redirected for Bramante’s restoration of St. Peter’s.

The initial design planned for a three-level freestanding building with 40 sculptures. Following the death of the Pope in 1513, the project’s scope was gradually decreased until, in April 1532, a final contract stipulated a plain wall tomb with less than one-third of the figures originally envisioned.

The most renowned sculpture linked with the tomb is the figure of Moses, which Michelangelo finished in 1513 during one of the work’s occasional resumptions.

This, according to Michelangelo, was his most realistic creation. According to legend, after he finished it, he whacked the right knee and said, “Now speak!” since he thought that life was the only thing remaining within the marble. A scar on the knee is supposed to represent the imprint of Michelangelo’s hammer.

8. The Genius of Victory

The Genius of Victory is a Michelangelo marble sculpture created between 1532 and 1534 as part of a design for Pope Julius II’s tomb. It stands 2.61 meters tall and is presently housed in the Salone dei Cinquecento in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio.

The actual date of the statue’s execution is uncertain, however it is commonly associated with the project for Julius II’s mausoleum.

It is likely to have been intended for one of the lower niches of one of the final proposals for the tomb, perhaps that of 1532, for which the so-called Captives or “Provinces” presently housed at Florence’s Galleria dell’Accademia were also created.

The monument, on the other hand, may have been paired with a comparable pair of combatants, a clay model in the Casa Buonarroti – the so-called Hercules-Samson.

The statue’s age and assignment to the tomb project are based on aesthetic aspects that connect the work to the Captives: the twisting of the body and the powerful anatomy, as well as similar dimensions.

In addition, the head is crowned with oak leaves, a nod to the Della Rovere insignia. The sculpture does not depict a battle scene, but rather a metaphor of triumph.

It displays the victor dominating the submissive loser with tremendous dexterity, with one leg blocking the captive’s folded and chained torso.

The victorious young guy is gorgeous and graceful, but the controlled man is elderly, bearded, and clothed in the clothing of an antique Roman warrior.

The surfaces are expressively handled to emphasize the contrast between the two figures: the youthful polished to perfection, and the ancient rough and imperfect, preserving the compacted boulder-like hardness of the massive stone from which it was created.

9. Rebellious Slave

Michelangelo’s Rebellious Slave is a 2.15m high marble statue from 1513. It is presently on display in the Louvre in Paris.

The Louvre’s two “slaves” originate from the second version of Pope Julius II’s tomb, which was commissioned by the Pope’s heirs, the Della Rovere, in May 1513.

Despite the fact that the early designs for a massive tomb were scrapped, the construction was nonetheless grandiose, with a hallway elaborately ornamented with sculpture, and Michelangelo was immediately assigned to the project.

The two Prigioni (renamed “slaves” only in the nineteenth century) were among the earliest pieces produced, intended for the bottom half of the funeral monument, adjacent to the pillars that framed the niches housing the Victories.

Their positions were chosen by the necessities of this architectural environment, thus they had a strong impact from the front, but the side views garnered less attention than normal.

A letter from Michelangelo to Marcello dei Covi confirms the dating of the two sculptures, in which he mentions a viewing by Luca Signorelli in his Roman villa as he worked on “a figure of marble, standing four cubits high, with its hands behind its back.”

The “Rebellious Slave” is seen contorting his body and twisting his head in an attempt to liberate himself from the fetters that restrain his hands behind his back.

With his elevated shoulder and knee, he gave the sense that he was advancing towards the observer, which would have added to the spatial look of the monument.

10. Dying Slave

The Dying Slave is a sculpture sculpted between 1513 and 1516 to accompany another figure, the Rebellious Slave, at Pope Julius II’s grave. It is a marble statue that is 2.15 meters (7′ 4″) tall and is housed in the Louvre in Paris.

Fourteen replicas of the Dying Slave decorate the top floor of Paris’s 12th arrondissement police station.

Despite its Art Deco appearance, the building was completed in 1991 by architects Manuel Nez Yanowsky and Miriam Teitelbaum.

11. Risen Christ, Cristo della Minerva

The Risen Christ, or Cristo della Minerva in Italian, is a marble sculpture completed in 1521. It is also known as Christ the Redeemer or Christ Carrying the Cross. It’s to the left of the main altar of Rome’s Santa Maria sopra Minerva church.

Metello Vari, a Roman aristocrat, commissioned the piece in June 1514, specifying merely that the naked standing figure hold the Cross in his arms, but leaving the composition largely to Michelangelo.

Around 1515, Michelangelo began working on a roughed-out version of this statue at his workshop in Macello dei Corvi, but he abandoned it when he found a black vein in the white marble.

In 1519-1520, a new version was rapidly inserted to fulfill the contract’s stipulations. Michelangelo worked on it in Florence, and the trip to Rome and finishing touches were assigned to an apprentice, Pietro Urbano; however, the latter damaged the work and had to be replaced swiftly by Federico Frizzi.