Since antiquity, marble has been the medium of choice for stone monumental sculpture, since it has various benefits over its more prevalent geological “father” limestone, including the capacity to absorb light a short distance into its surface before dispersing it underground.

This provides the material a silky, appealing aspect that is ideal for mimicking human skin, which may also be polished.

White marbles are often used for sculpting, whereas colorful marbles are used for several architectural and aesthetic applications.

If not exposed to acid rain or saltwater, the degree of hardness is optimal for carving without excessive difficulty while yet producing a very durable product.

Famous individual kinds and quarries include Parian marble from Paros, which was used for the Venus de Milo and many other Ancient Greek sculptures, and Pentelic marble from near Athens, which was utilized by the Romans for the majority of the Parthenon statues.

The Romans used Carrara marble from northern Italy extensively until recent decades, when the pure white statuario quality became scarce. This was used by Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists, and was subsequently disseminated worldwide.

Famous Marble Statues

1. Venus de Milo – Alexandros of Antioch

In 1820, a Greek peasant farmer uncovered one of the most famous sculptures from antiquity on the island of Milos.

It was the French minister to Greece, Marquis de Rivière, who found and bought the statue, and it was he who ultimately delivered it to King Louis XVIII. After being buried on the little Greek island, the monument was brought to Paris and placed in the Louvre Museum two years later.

It’s known as Venus de Milo, although scholars have given it a variety of other names. One of the most iconic ancient Greek sculptures is this one, which features a female figure with no upper arms.

Aphrodite is supposed to have been shown in the sculpture, but the Roman version of the goddess, Venus, is engraved on it.

For the first time, a painting unearthed recently has been found to be the original, rather than a replica.

One of the most remarkable pieces from the first or second century B.C. is her form and the shawl that covers her lower half.

2. The Veiled Christ – Giovanni Strazza

Giuseppe Sanmartino’s 1753 marble sculpture, The Veiled Christ, is displayed in Naples, Italy’s Cappella Sansevero.

The Veiled Christ is recognized as one of the most amazing sculptures in the world, and it is supposed to have been created by alchemy. Sculptor Antonio Canova, who tried to buy the sculpture, stated he would willingly give up ten years of his life to make a similar masterpiece.

Veiled Antonio Corradini, a sculptor who specialized in veiled statues, was first charged with constructing Christ. Corradini, on the other hand, died not long after, having only created a clay bozzetto (today displayed at the Museo Nazionale di San Martino).

Giuseppe Sanmartino was tasked with building “a marble statue sculpted with maximum realism, depicting Our Lord Jesus Christ in death, draped in a transparent shroud carved from the same block of stone as the statue.”

Sanmartino made a work in which the dead Christ lies on a couch, shrouded in a veil that perfectly suits his shape. The Neapolitan sculptor’s ability is evident in his outstanding depiction of Christ’s sorrow during the crucifixion through the curtain. Jesus’ face and chest show signs of agony.

Sanmartino engraved pictures of the crucifixion devices at Jesus’ feet, adding detail to the marble block: pliers, chains, and the crown of thorns.

The sculptor’s excellent portrayal of the veil has been the subject of a story in which the original commissioner, the renowned scientist and alchemist Raimondo di Sangro, demonstrates how to transform linen into crystalline marble.

Awestruck by the covered artwork, many visitors to the Cappella incorrectly imagined it was the result of the prince’s alchemical “marblification” over the years. He was said to have draped an actual veil over the sculpture and, over time, turned it into marble using a chemical method.

In fact, a detailed study shows that the sculpture was entirely made of marble. This is corroborated by letters written at the time of its establishment. The Bank of Naples’ Historical archive has a payment receipt to Sanmartino dated 16 December 1752 and signed by the prince.

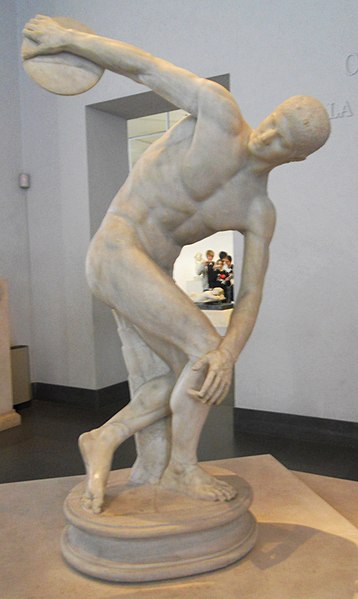

3. Discobolus of Myron

Discus was a popular sport in ancient Greece and played an important role in the early Olympic Games. Despite the fact that there are multiple sculptures and bronze statues portraying this single work, scholars believe that the original sculpture has been lost to history.

The statue is known as The Discobolus of Myron, or the Discus Thrower, and is thought to have been sculpted somewhere between the 4th and 5th century B.C. in Greek history.

The first duplicate of this renowned work was unearthed in 1781, and it is thought to be a replica of a sculpture carved by Myron, an Athenian artist who flourished in the 5th century B.C. Many more variants of this specific statue have been found after it was found.

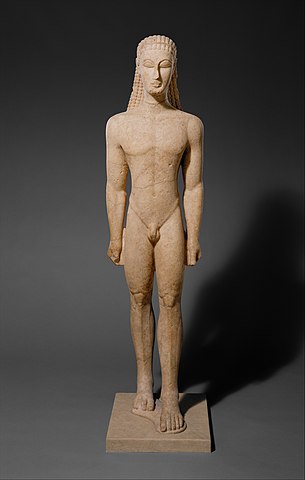

4. New York Kouros

The New York Kouros is an early example of Greek life-sized sculpture. The marble statue of a Greek boy, kouros, was sculpted in Attica and is removed from the block of stone. It gets its name from its present home, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

During the archaic era of Ancient Greece, this kouros was carved in Attica. It was a period when Greece was divided into several city-states. Throughout the 6th century BC, Greek painters created more lifelike depictions of the human form.

Greece was emerging from an orientalizing era, in which Ancient Greece was progressively affected by numerous eastern and southern cultures.

This explains why the statue has a more natural appearance than prior Greek art while yet retaining certain orientalizing features—particularly the Egyptian influence, with whom they had extensive interaction. Kouroi were often utilized as tomb markers or deity dedications.

5. Belvedere Torso – Apollonius of Athens

One of Rome’s most iconic sculptures is also one of the most intriguing works in the city. The Belvedere Torso sculpture is a large marble statue that measures more than 1.5 meters tall.

The actual date of completion is uncertain, although many art critics and experts formerly thought it may be as ancient as the first century B.C.

Many people thought the monument was Hercules, a legendary Greek and Roman figure famed for his tremendous feats of strength.

The Belvedere Torso is signed on the front of the base, along with some information about its identification. “Apollonios, son of Nestor, Athenian,” the signature reads.

Although it is just a fragment of a much bigger statue, this work was originally shown at the Vatican during the 1500s. Michelangelo was known to have adored the sculpture and often visited the Vatican to see it throughout his career.

6. Pietà – Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, better known as Michelangelo, was one of the most important artists of the Italian Renaissance and one of the best known. Because he was a talented painter, many people think he was one of the most important sculptors in history.

He made a lot of great art that hangs in the cathedrals in Rome and other big cities in Italy.

One of his best-known sculptures is called Pietà. This amazing statue, which was made in 1499, shows a scene in which Mary, the mother of Jesus, holds her son’s dead body in her arms.

The work was meant to be a memorial for the French ambassador to Rome, Cardinal Jean de Bilhères. When the sculpture was done, it was thought that it was too beautiful to only be used for funerals, so it was put in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City instead of being used for that.

The sculpture is probably best known for how much detail Michelangelo was able to put into it. There is incredible, lifelike precision in everything from Jesus’ hands to Mary’s face and even her clothes and robes.

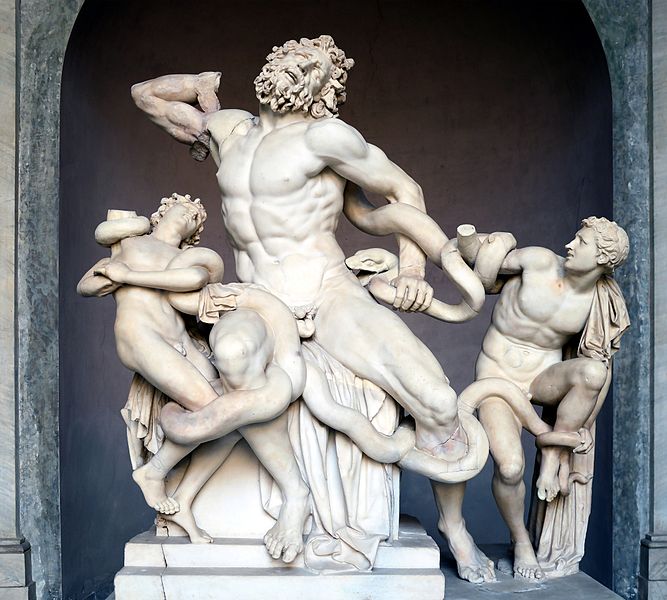

7. Laocoön and His Sons

One ancient Greek work has more history than any other. It dates back to the time it was made, as well as the height of the Renaissance in Italy.

In ancient history, Pliny the Elder talked about a statue called Laocoon and his sons, which is thought to have been made around 200 B.C. People who write about history say that the statue was on show in the palace of Roman Emperor Titus.

The historian said that this piece was said to have been made by three Rhodesian sculptors, Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus, who worked together. Ancient Greece had a lot of unique art. This statue is one of them because it tells the story of Laocoon, who was a priest of the Greek god Poseidon.

The story is about Laocoon and how he tried to find out how the Trojan horse was made. The priest’s own sons are said to have killed him when they found out about his plans to expose the ruse that helped the Greeks get into Troy.

The statue was found in a vineyard in Florence in 1506. Pope Julius II and Michelangelo were there to see it.

8. David – Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was a notable figure during the Italian Renaissance, which lasted from the 15th through the 16th century. Michelangelo was well recognized as a painter, but it was his sculpting that captured the attention of everyone who observed his work.

Michelangelo’s finest masterpiece, according to critics and history, is his work known as David. The artist created this larger-than-life monument of the well-known Biblical king and hero in 1504.

Michelangelo was commissioned to create the piece by the city of Florence, Italy, where he had previously created a number of renowned sculptures.

Also Read: Famous Statues in Florence

The sculpture was originally supposed to be placed along the roofline in front of the city’s cathedral, but when completed, it was judged too stunning to be retained at that distance.

Rather than that, the sculpture was erected in front of the city’s headquarters, the Palazzo Vecchio. The masterpiece, which was carved from marble, is regarded as one of the most realistic portrayals ever created.

9. Parthenon Marbles

The Elgin Marbles, sometimes referred to as the Parthenon Marbles, are a group of Classical Greek marble sculptures created under the direction of architect and sculptor Phidias and his associates.

They are ancient components of the Parthenon and other holy and ceremonial monuments constructed on Athens’ Acropolis in the fifth century BCE. The collection is housed in the purpose-built Duveen Gallery at the British Museum.

Between 1801 and 1812, agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin took over half of the Parthenon’s surviving sculptures, as well as those from the Propylaea and Erechtheum, and had them transferred to Britain by sea.

Elgin claimed as justification for this that he had secured an official proclamation (a firman) from the Sublime Porte, the Ottoman Empire’s central government, which at the time was the legal owner of the statues as ruler of Greece.

Despite its richness of records from the same time, this firman has not been discovered in the Ottoman archives, and its credibility is contested. The Acropolis Museum exhibits a piece of the full frieze, oriented correctly and visible from the Parthenon, with the missing components’ positions clearly identified and room reserved in case they are restored to Athens.

In Britain, some defended the Earl’s purchase of the collection, while others, such as Lord Byron, compared it to vandalism or looting.

Elgin surrendered the Marbles to the British government in 1816 after a public discussion in Parliament and its eventual exoneration of Elgin. They were later transferred to the British Museum’s trusteeship, where they are presently on exhibit in the newly constructed Duveen Gallery.

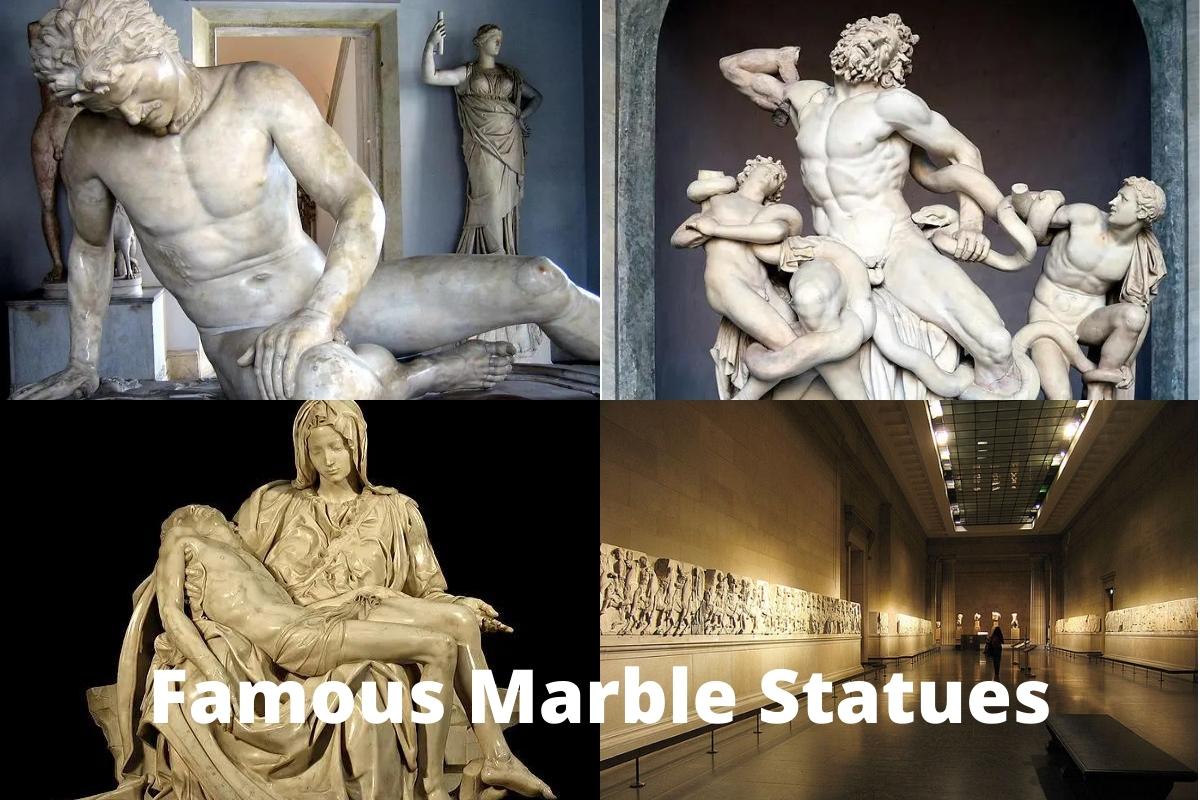

10. Dying Gaul

In the second and third century B.C., the Roman Empire was surrounded by opponents due to their dominance over a large portion of the territory bordering the Mediterranean Sea.

The Roman Empire’s troops waged bloody conflicts with the indigenous peoples of western Europe known as the Celts or Gauls. The Dying Gaul, or Dying Galatian, is a monument honouring these heroes and the conflicts the Roman Empire fought with them.

This statue is said to have been created between 200 and 350 B.C. and is almost certainly a replica of an older piece that has since been lost to history. The life-size white marble statue represents an extraordinarily realistic naked Gaul soldier sitting on the ground, suffering from a sword wound to his lower chest.

The painting is regarded to be particularly realistic since the Gauls were known to battle nude and often wore distinctive haircuts and mustaches similar to those represented as a sign of prestige and vigor. The soldier is seated on his shield, his weapon tucked under him.