Victorian art refers to the diverse types of painting that flourished in the United Kingdom during Queen Victoria’s reign (1837–1901).

Victoria’s early reign was marked by fast economic progress and social and political revolution, which elevated the United Kingdom to the ranks of the world’s most powerful and advanced countries.

Many artists anticipated that their works would bring social concerns to the attention of audiences with the clout and resources to act. Many Victorian artists were assured a big and influential audience by displaying their work at prominent exhibition sites.

Paintings highlighting modern social issues grew in popularity, displacing historical paintings, landscapes, and portraits that had previously dominated shows.

The introduction of photography at the Great Exhibition of 1851 caused enormous changes in Victorian art, with Queen Victoria being the first British monarch to be photographed.

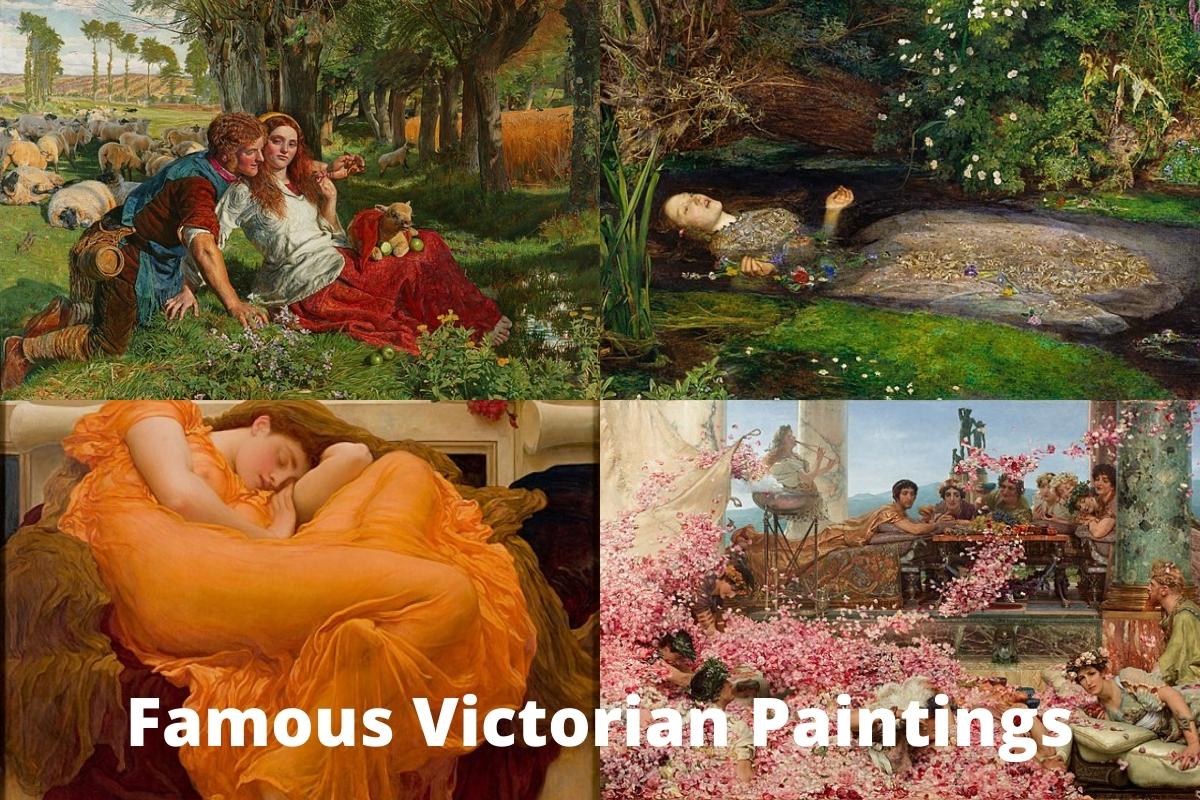

Famous Victorian Paintings

1. Ophelia – John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais painted Ophelia between 1851 and 1852, and it is now part of the Tate Britain collection in London. In the play Hamlet, the character Ophelia sings before drowning in a river in Denmark.

For its beauty, accuracy, and impact on painters from John William Waterhouse and Salvador Dali to Peter Blake and Ed Russa, it has been hailed as one of the most significant works of the mid-nineteenth century by art historians and collectors alike.

Also Read: Famous British Paintings

While floating on a river, the picture portrays Ophelia singing. In Hamlet, the action is depicted in a speech by Queen Gertrude in Act IV, Scene VII.

It depicts a lady who has spent her whole life hoping for happiness, only to realize her fate on the point of death: Pre-Raphaelite painters often depicted women in vulnerable positions.

Millais was known for his use of vivid colors, meticulous attention to detail, and unwavering adherence to the natural world’s truths.

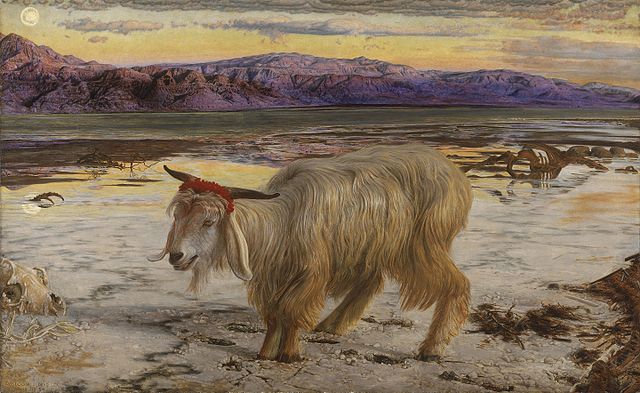

2. The Scapegoat – William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt painted The Scapegoat (1854–1856), which represents the biblical “scapegoat” from Leviticus.

Atonement Day, a goat was driven off with its horns wrapped in scarlet fabric to symbolise the community’s misdeeds.

At the Dead Sea, Hunt began painting and continued in his London studio once he returned to the United Kingdom. Manchester Art Gallery has a smaller version of the piece with a dark-haired goat and a rainbow, whereas the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight has a bigger version with a light-haired goat.

Despite the fact that they were both made at the same time, the smaller Manchester version is considered “preliminary” to the bigger Lady Lever version, which was on display.

3. Flaming June – Frederic Leighton

Flaming June is an 1895 artwork by Sir Frederic Leighton. It is usually regarded as Leighton’s greatest achievement, painted with oil colors on a 47-by-47-inch square canvas and demonstrating his classicist inclination.

It is considered that the lady shown relates to the Greeks’ often carved representations of sleeping nymphs and naiads.

Flaming June vanished in the early 1900s and was rediscovered in the 1960s. It was auctioned soon after that, at a period considered to be difficult for selling Victorian-era paintings, but it did not sell for its low reserve price of US$140 (the equivalent of $1,126 in contemporary standards). It was swiftly acquired after the auction by the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Ponce, Puerto Rico.

4. Lady Agnew of Lochnaw – John Singer Sargent

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw is a portrait of Gertrude Agnew, the wife of Sir Andrew Agnew, 9th Baronet, painted in oil on canvas. The artwork was commissioned in 1892 and finished the following year by American portrait artist John Singer Sargent.

Also Read: John Singer Sargent Famous Paintings

It is held by the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland, and measures 127 101 cm (50.0 39.8 in). In 1925, the Cowan Smith Bequest Fund donated it to the museum.

Lady Agnew is sat in an 18th-century French Bergère, and the back of the chair is employed as a “curving, supporting space to confine the body, giving a particular, languid grace,” according to art historian Richard Ormond.

Sargent envisioned her in a three-quarter length stance, clothed in a white gown with a silk mauve belt around her waist as an accent. The wall behind her is covered in blue Chinese silk.

She stares at the picture directly and appreciatively, her countenance conveying the idea that she is having a “intimate discussion” with others who are looking at it.

5. The Roses of Heliogabalus – Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Sir Lawrence Alma-1888 Tadema’s painting The Roses of Heliogabalus depicts the youthful Roman emperor Elagabalus (203–222 AD) having a dinner.

The picture shows a (possibly fictional) occurrence from the Augustan History of the Roman Emperor Elagabalus, also known as Heliogabalus (204–222).

Despite the Latin’s reference to “violets and other flowers,” Alma-Tadema shows Elagabalus suffocating his unwitting guests with rose petals released from a fake ceiling.

Sir John Aird, 1st Baronet commissioned the picture in 1888 for £4,000. Because roses were out of season in the UK, Alma-Tadema is said to have had rose petals brought from the south of France every week for the four months it was painted.

6. God Speed – Edmund Leighton

God Speed is a painting by British artist Edmund Leighton that depicts an armored knight heading for battle and leaving his sweetheart behind. In 1900, the artwork was shown at the Royal Academy of Arts.

God Speed was the first of numerous paintings on the topic of chivalry by Leighton in the 1900s, including The Accolade (1901) and The Dedication (1902). (1908).

Leighton made a last-minute alteration in the studio before delivering the picture to the Royal Academy. He scrounged together a week’s worth of labor and produced the needed alteration in two hours.

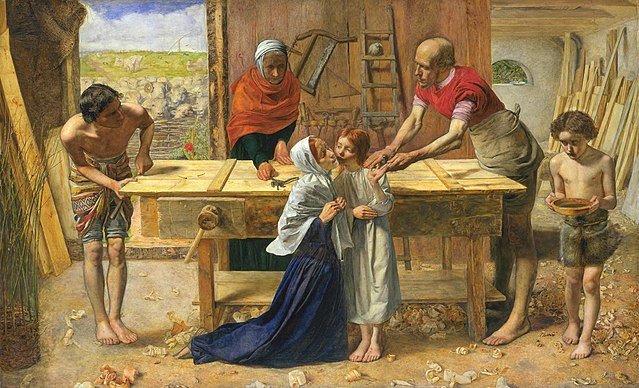

7. Christ in the House of His Parents – John Everett Millais

Christ in the House of His Parents (1849–50) by John Everett Millais depicts the Holy Family in Saint Joseph’s carpentry workplace. When it was initially shown, the artwork sparked outrage, triggering several unfavorable reviews, including one penned by Charles Dickens.

It brought the previously unknown Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to public attention and was an important contribution to the debate over Realism in the arts.

When it was originally shown, the artwork sparked outrage due to its accurate representation of a carpentry workplace, particularly the grime and debris on the floor. This was in stark contrast to the common depiction of Jesus, his family, and his disciples dressed in Roman togas.

The negative remarks popularized the Pre-Raphaelite movement and sparked a discussion regarding the link between modernity, realism, and medievalism in the arts.

Despite his dislike for the picture, critic John Ruskin endorsed Millais in a letter to the newspaper and in his lecture “Pre-Raphaelitism.” The use of symbolic realism in the painting sparked a larger trend in which composition and topic were mixed with meticulous observation.

8. The Lady of Shalott – John William Waterhouse

The Lady of Shalott is an 1888 artwork by English painter John William Waterhouse. It depicts the conclusion of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s 1832 poem of the same name.

Waterhouse depicted this figure three times, in 1888, 1894, and 1915. It is one of his most renowned paintings, in which he inherited much of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s style, despite the fact that Waterhouse was painting many decades after the Brotherhood broke up during his adolescence.

Sir Henry Tate presented the Lady of Shalott to the public in 1894, and it is now on exhibit at Tate Britain, London, in room 1840.

Also Read: London Paintings

One of John William Waterhouse’s most renowned works is The Lady of Shalott, an 1888 oil-on-canvas painting. Waterhouse depicted this figure three times, in 1888, 1894, and 1915.

It depicts a scene from Tennyson’s poem in which the poet describes the plight and predicament of a young woman, loosely based on the figure of Elaine of Astolat from medieval Arthurian legend, who yearned with unrequited love for the knight Sir Lancelot, who was isolated under an unknown curse in a tower near King Arthur’s Camelot.

9. Proserpine – Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Proserpine is an oil painting on canvas by English artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti that was completed in 1874 and is currently housed at Tate Britain. Rossetti started working on the picture in 1871 and finished at least eight different versions, the latest of which was completed in 1882, the year before his death.

Charles Augustus Howell was promised early editions. The artwork addressed in this article is the so-called seventh version commissioned by Frederick Richards Leyland, which is presently on display at the Tate Gallery, with a very similar final version on display in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

The artist depicts the Greek goddess who resides in the underworld during the winter in his trademark Pre-Raphaelite manner. Despite the fact that Rossetti placed the year 1874 on the painting, he worked on it for seven years on eight consecutive canvases before completing it.

His Proserpine, like his model Jane Morris, is a stunningly attractive lady with delicate facial features, thin hands, and beautifully pale complexion highlighted by her rich raven hair. Rossetti painted it during a period when his mental health was in jeopardy and his obsession with Jane Morris was at its peak.

10. The Hireling Shepherd – William Holman Hunt

The Hireling Shepherd (1851) is a picture by William Holman Hunt, a Pre-Raphaelite artist. It depicts a shepherd who ignores his flock in favor of a pretty rural girl, to whom he reveals a death’s-head hawkmoth. The image’s significance has been hotly contested.

Hunt created the painting while living and collaborating with John Everett Millais, who was also painting Ophelia at the time at the Hogsmill River in Ewell, Surrey.

Both paintings represent English countryside vistas in which the innocence is disrupted by minor but deeply disturbing transgressions of natural equilibrium.