A Serigraph is an alternative name for silkscreen printing that was coined to distinguish it’s uses in the fine art world from that of the commercial printing world.

Many famous pop art artists such as Andy Warhol and Peter Max used serigraphy as their main medium as pop art was in essence a form of commercial art.

Serigraphs are often confused with lithographs, but the process involved is quite different.

What is a Serigraph?

A Serigraph simply refers to silkscreen printing. “Seri” means “silk” in Latin, and “graphos” means “writing” in Ancient Greek. A serigraph is an interpretation of a given image that’s created through the silkscreening process.

Serigraphy Printing Process

The process of creating a serigraph is labor-intensive; completing an artistic project can take many weeks. Here is a step-by-step breakdown of the process.

First, before an artist embarks on creating a rendition of a given image, they consult the creator of the original image. Sometimes artists think of a serigraph as an original work of art rather than a recreation of an existing image. An artist can create a vibrant new image even by slightly altering the image or emphasizing particular design elements and colors.

Separate Colors

The next step is to break down the original portrait into separate colors. The process of separating colors entails analyzing the original image, selecting the colors that will be printed, one at a time, and then painting a black ink replica of each of those colors.

The process of color separation was initially done by hand, using blank India ink, paintbrushes, and a clear plastic film, but now artists rely on computers. Thanks to computers, color separation is now less laborious, but the experience and the eye of the chromist (a color separation expert) are still valuable. Chromists incorporate the subtleties of texture and color to computer-generated color separation.

To create a serigraph, the printer forces ink through a chain of meshed silkscreens. Silkscreens are made of fine silk, but synthetic materials like polyester or nylon are also often used. The mesh is stretched firmly on an aluminum or wooden frame, and it’s usually covered with a thin layer of photo-sensitive material.

To create a separation, a chromist paints an opaque medium onto a transparent acetate or Mylar piece. The film is then placed over the photo-emulsion coated silkscreen, which is then placed under powerful light.

The emulsion that gets exposed to light is hardened, or ‘cured,’ and the areas covered by the opaque separation remain soft and uncured. The printer then washes the ‘uncured’ sections of the silkscreen using a high-pressure spray gun.

Once the screen gets light exposure, is washed, and dried, the printer blocks out ‘pinholes’ or any specs that may have been created by stray dirt. The screen is then placed on a press that’s calibrated to shift upward and downward with consistent registration. The precisely calibrated printer enables the printer to reproduce identical color layers in each print.

When a printer is making, say, 100 prints, they paint one color at a time, so the screen is used on all the 100 prints before replacing it by another screen of a different color.

Prepare the Ink

Before a printing session, the color mixer prepares suitable ink for each screen. The chromist and the color mixer collaborate to create the desired artistic effect. To create the ideal ink for each color separation, they consider the various aspects of the ink including hue, viscosity, opacity/transparency, and intensity.

Translucent or transparent colors, for instance, can create various effects and colors when printed on various fields of color. Opaque inks can create a given physical texture or cover certain unwanted areas. The chromist has to think through all these variances to limit the number of screens or separations used in the process. Similarly, the printer has to evaluate various factors, the most important consideration being the type of mesh used on each screen.

Choose the Right Screens

When a printer wants to print heavy texture or large fields, a coarse mesh screen is ideal. Conversely, if a painter wants to paint fine detail, they need a screen made of fine mesh. A printer can also control print quality with various types of squeegees.

Different variants of squeegees come in different materials and hardness; they are, therefore, adapted to various types of technical situations. A painter can also create many effects using stroke, pressure, and angle.

Each color separation is printed separately, one shade at a time, starting with the base color and concluding with a finishing coat. After the painting of each separation, the print is air-dried before the next color run. The whole process can take up to several months, depending on the complexity of the serigraph being printed.

Once the printing process is over, the artist verifies each print, and then numbers and releases the prints to galleries. If a print has the notation 1/150, this means it’s the first of 150 serigraphs in the edition. By numbering and signing the print, the artist ensures that the number of serigraphs will never exceed the number of prints originally designated for that particular edition.

History of Serigraphy

The roots of serigraphy stretch deep into ancient history; the medium was first put into use in Japan and China where it was used to apply stencils to screens and fabrics. There are examples of silkscreening that date back to the Song Dynasty (an epoch that started in 960 AD and ended in 1279 AD).

Artists and artisan in Europe adopted the technique in the 15th century and developed it for a wide range of artistic and decorative applications. Modern silkscreening, however, took off early on in the 20th century when Samuel Simon from Manchester, England, patented the process which was quickly adopted for commercial use.

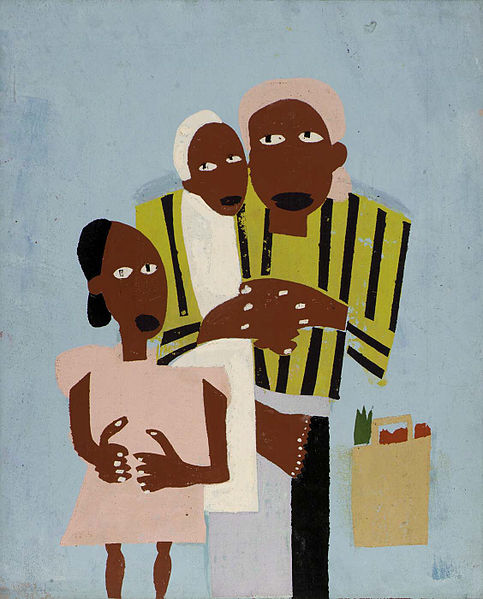

Conversely, fine art serigraphy was born in the mid-1930s when its artistic potential was explored by Works Progress Administration artists, a group of American artists.

But it was in 1960, with the initiation of Op Art and Pop Art, that serigraphy matured as an art form. Artists like Andy Warhol, Josef Albers, Richard AnuzkiwiCZ, Robert Rauschenberg, and Peter Max viewed its commercialism –which had earlier on limited its artistic acceptance – as an advantage.

These artists, and others, tapped into serigraphy’s cultural associations and technical potential to create art that resonated with the zeitgeist of the time.

Serigraph vs Silkscreen

Serigraphy and silkscreening denote the same printing method, and thus they are often used interchangeably. However, the term serigraph was coined to distinguish fine art screen prints from commercial screenprinting processes like the use of automated machines to print on t-shirts.