The relationship between Roman and Greek art complicates the study of Roman sculpture. Many of the most renowned Greek sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere and the Barberini Faun, are only known via Roman Imperial or Hellenistic “copies.”

Art historians often interpreted this replication as reflecting a narrowness of the Roman creative imagination, but in the late twentieth century, Roman art started to be reevaluated on its own terms: certain perceptions about the nature of Greek sculpture may in fact be founded on Roman artistry.

Roman sculpture’s strengths include portraiture, where they were less concerned with the ideal than the Greeks or Ancient Egyptians and created exceptionally characterful pieces, and narrative relief scenes.

In contrast to Roman painting, which was extensively practiced but has virtually all been destroyed, examples of Roman sculpture are numerous.

While most Roman sculpture remains more or less intact, it is sometimes damaged or incomplete; life-size bronze sculptures are even more uncommon, since most have been recycled for their metal.

Most sculptures were originally significantly more realistic and frequently highly colored; the bare stone surfaces present now are the result of pigment loss over the millennia.

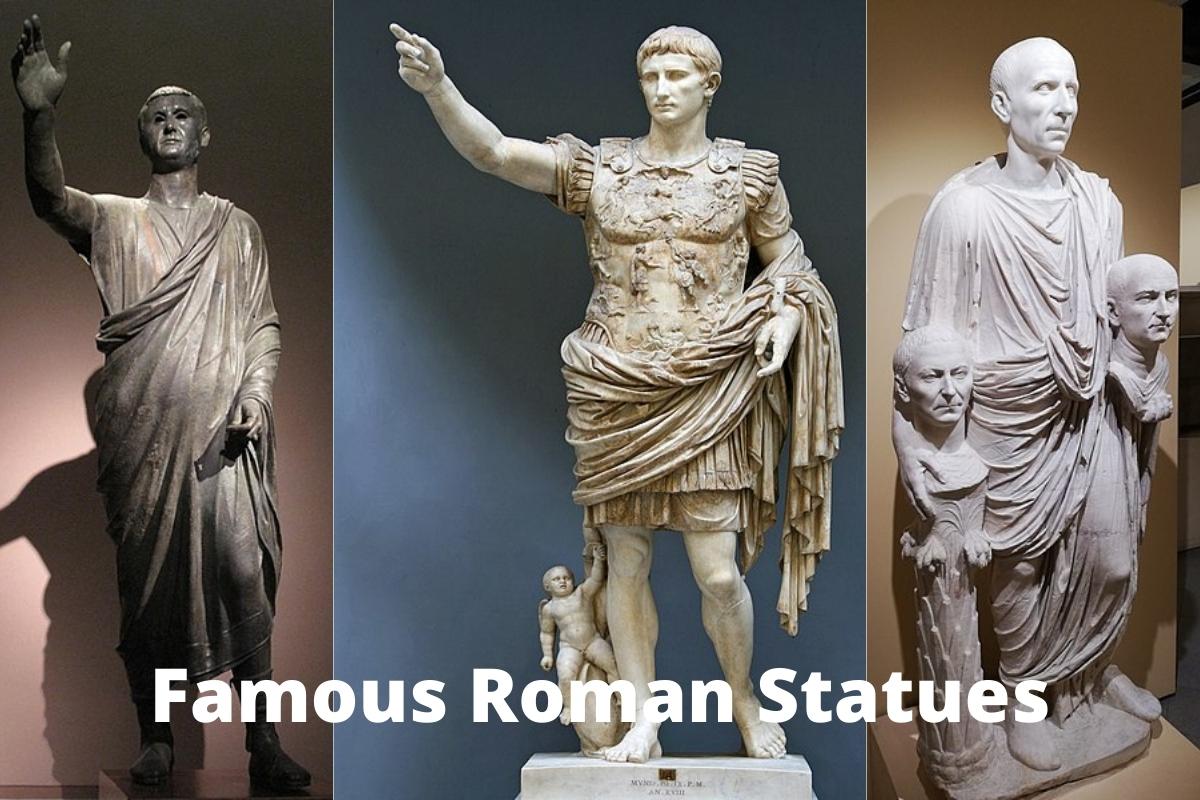

Famous Roman Statues

1. Augustus of Prima Porta

Augustus of Prima Porta is a full-length picture of Augustus Caesar, the Roman Empire’s first emperor. The marble statue is 2.08 meters tall and 1,000 kilograms in weight.

The statue was unearthed on April 20, 1863, during archaeological excavations led by Giuseppe Gagliardi at the Villa of Livia in Prima Porta, which belonged to Augustus’ third and last wife, Livia Drusilla.

After Augustus’ death in AD 14, Livia withdrew to the estate. The statue was initially made public by German archeologist G. Henzen, who published it in the Bulletino dell’Instituto di Corrispondenza Archaeologica (Rome 1863).

The figure, carved by experienced Greek sculptors, is said to be a replica of a lost bronze original shown at Rome. The Augustus of Prima Porta is presently on exhibit at the Vatican Museums’ Braccio Nuovo (New Arm).

It has become the most renowned of Augustus’ portraits and one of the most famous sculptures of the ancient world since its discovery.

2. Farnese Hercules

The Farnese Hercules is an antique Hercules statue that was possibly extended in the early third century AD and signed by Glykon, who is otherwise unknown; his name is Greek, although he may have worked in Rome.

It is, like many other Ancient Roman sculptures, a copy or reproduction of a much earlier Greek original that was widely known, in this instance a bronze by Lysippos (or one of his circle) constructed in the fourth century BC.

This original lasted almost 1500 years until being melted down by Crusaders at the Sack of Constantinople in 1205. The bigger duplicate was created for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (dedicated in 216 AD), where the statue was rediscovered in 1546 and is currently housed in Naples’ Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

Also Read: Famous Buildings in Rome

The heroically sized Hercules is one of antiquity’s most renowned sculptures, and it has permanently imprinted the image of the epic hero in the European mind.

The Farnese Hercules is a large marble statue based on a lost original that was reproduced in bronze using a technique known as lost wax casting. It represents a powerful, though tired, Hercules resting on his club, which is covered with the pelt of the Nemean lion.

In mythology, Heracles’ first mission was to slay the lion. He has recently completed one of The Twelve Labors, as indicated by the apples of the Hesperides he carries behind his back.

Also Read: Famous Statues in the Louvre

The type was widely known in antiquity, and a Hellenistic or Roman bronze reduction discovered in Foligno is housed in the Musée du Louvre, among many other variations. Overlooking the Museum of the Ancient Agora in Athens is a modest Roman marble replica.

3. The Orator

The Orator, also known as L’Arringatore (Italian), is a late second or early first century BC Etruscan bronze sculpture.

Aulus Metellus was an Etruscan senator from Perugia or Cortona in the Roman Republic. The Aulus Metellus sculpture was discovered in 1566; the precise site is unknown, although all sources agree it was discovered at or near Lake Trasimeno in the province of Perugia, on the boundary between Umbria and Tuscany, 177 kilometers (110 miles) from Rome.

The statue is 179 cm tall and is dressed in a toga exigua, which consists of a short-sleeved tunic beneath a close-fitting toga thrown over the left arm and shoulder while leaving the right arm free for mobility.

The hem begins above the left ankle and runs diagonally up to just above the right calf. The statue also wears calceus senatorius boots, a form of red leather footwear used by senators and high ranking magistrates. The statue is in a contrapposto position, with one leg bearing the majority of its weight.

The Aulus Metellus statue was created as a votive gift. A votive offering is an item presented to any panhellenic deity in exchange for the successful fulfillment of a petition.

This item might be anything from a homemade effigy to a commissioned statue if the donor of the gift is affluent. The statue’s status as a votive offering is debatable, with some historians claiming it was an honorary statue designed for public display rather than a gift to the gods.

4. Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

The Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Monument is an antique Roman equestrian statue located on Capitoline Hill in Rome, Italy. It is 4.24 m (13.9 ft) tall and constructed of bronze.

Although the emperor is mounted, it has many parallels to standing Augustus monuments. The original is on exhibit at the Capitoline Museums, and the one presently standing in the Piazza del Campidoglio is a copy constructed in 1981 after the original was removed for repair.

Around 175 AD, the statue was constructed. The Roman Forum and Piazza Colonna (where the Column of Marcus Aurelius stands) have been offered as possible locations. However, it was discovered that the original location had been turned into a vineyard during the early Middle Ages.

Also Read: Famous Italian Sculptures

Although there were numerous equestrian statues, they seldom lasted since it was customary practice in the late empire to melt down bronze statues for reuse as material for coinage or new sculptures.

It is one of only two surviving bronze sculptures of a pre-Christian Roman emperor; the Regisole, which was destroyed during the French Revolution, might have been another.

The equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome owes its survival on the Campidoglio to the popular confusion of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor, with Constantine the Great, the Christian emperor; in fact, more than 20 other bronze equestrian statues of various emperors and generals had been melted down since the end of the Imperial Roman era.

The figure appears on the reverse of a Marcus Aurelius aureus coin produced in 174 AD. The figure appears on the back of the current Italian €0.50 coin, created by Roberto Mauri.

The statue was formerly covered with gold. According to an ancient local legend, the statue will become gold again on the Day of Judgment.

5. Colossus of Constantine

The Colossus of Constantine was a massive, life-size acrolithic statue of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (c. 280–337) commissioned by himself that originally filled the west apse of the Basilica of Maxentius on the Via Sacra, near the Forum Romanum in Rome.

Surviving sections of the Colossus may currently be seen in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, which is now part of the Capitoline Museums and is located on Capitoline Hill, above the west end of the Forum.

The Colossus’ huge head, arms, and legs were carved from white marble, while the remainder of the body was made of a brick core and a timber structure, maybe plated in gilded bronze.

The sitting, enthroned figure would have stood roughly 12 meters (40 feet) tall based on the size of the surviving components. The head is over 212 meters tall, and each foot is nearly 2 meters long.

The enormous head is carved in the customary, abstract Constantinian style (‘hieratic emperor style’) of late Roman portrait statues, yet the rest of the body is realistic, down to calloused toes and bulging forearm veins.

The head’s larger-than-life eyes, which look into eternity from a rigorously impersonal, frontal face, may have been intended to depict the Emperor’s transcendence of his otherworldly essence over the human realm.

6. Statue of Antinous (Delphi)

The Antinous Statue at Delphi is an antique statue discovered during excavations at Delphi.

Antinous was a young Greek of great beauty from Bithynia who became the Roman emperor Hadrian’s cherished partner or lover before dying in the Nile under unexplained circumstances.

Stricken by Antinous’ death, Hadrian, a great lover and devotee of ancient Greek antiquity, as well as a patron of the Oracle of Delphi, ordered that statues of the handsome young man he had so passionately loved be constructed in all shrines and towns across his vast empire.

Furthermore, he commanded the formation and institution of Games in honor of Antinous, who was afterwards adored and worshiped as a deity. After his death in A.D. 130, a statue of Antinous was constructed inside the sanctuary of Delphi, and it was one of the most magnificent and outstanding cult sculptures.

7. Togatus Barberini

Togatus Barberini is a Roman marble sculpture from the first century AD[1] depicting a full-body figure called a togatus clutching the skulls of departed ancestors in each hand.

It is housed in Rome, Italy, in the Centrale Montemartini (formerly in the Capitoline Museums). There is nothing known about this sculpture or who it portrays, although it is thought to be a portrayal of the Roman burial tradition of producing death masks.

Little is known about the identities of persons shown in the sculpture, although the sort of shoes worn by the center figure marks them as a member of the Roman aristocratic elite.

Many hypotheses have arisen as a result of this minor piece of information in conjecture about the real identity of the center figure, but little proof has been presented to back up many of these assertions, so they remain merely speculations.

8. Bust of Emperor Lucius Verus

Lucius Aurelius Verus (15 December 130 – January/February 169) was a Roman emperor who reigned with his adopted brother Marcus Aurelius from 161 until his death in 169.

He belonged to the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. Verus’ succession, along with Marcus Aurelius’, was the first time the Roman Empire was controlled by several emperors, an increasingly typical event in the Empire’s later history.

He was the firstborn son of Lucius Aelius Caesar, Hadrian’s first adopted son and heir, and was born on December 15, 130. He was raised and schooled in Rome and served numerous political positions before ascending to the throne.

Also Read: Bust Sculptures

Following the death of his original father in 138, he was adopted by Antoninus Pius, who was himself adopted by Hadrian. Later that year, Hadrian died, and Antoninus Pius ascended to the throne. Antoninus Pius ruled the empire until his death in 161, when he was succeeded by Verus and his adopted brother Marcus Aurelius.

As emperor, he spent the bulk of his reign directing the war with Parthia, which resulted in Roman victory and some territory gains.

After being involved in the Marcomannic Wars, he became sick and died in 169. The Roman Senate elevated him to the status of Divine Verus (Divus Verus).

9. Bronze of Trebonianus Gallus

Gallus bronze during his tenure as Roman Emperor, is the only near-complete full-size 3rd-century Roman bronze that has survived.

Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (206 – August 253) was the joint ruler of Rome with his son Volusianus from June 251 to August 253.

10. Venus in a Bikini

“Venus in a Bikini” is a Pompeii marble figurine depicting the goddess Aphrodite about to untie her sandal while resting her left arm on a figure of Priapus. 1st century AD, presently on exhibit in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples’ Secret Cabinet.

Aphrodite is nearly all nude, save for a corset held up by two pairs of straps and two short sleeves on the upper portion of her arm, from which a long chain extends to her hips and creates a star-shaped pattern at the level of her navel.

The ‘bikini,’ for which the figurine is famed, is achieved by the masterful use of the gilding method, which is also used on her crotch, the pendant necklace, and the armilla on Aphrodite’s right wrist, as well as on Priapus’ phallus.

Traces of red paint may be seen on the tree trunk, the Goddess’s lips, the short curling hair tied back in a bun, and the heads of Priapus and Eros.